Social mirror of Switzerland

The Swiss Association of Musicians was founded 125 years ago. A brief outline of its eventful history up to its dissolution eight years ago.

The Swiss Association of Musicians (STV) has been central to the development of contemporary music in Switzerland since it was founded in 1900. With annual Tonkünstler festivals, magazines, recordings and prizes, it shaped the canon and discourse until its dissolution in 2017. Its activities have been reflected in an archive, which has recently been made accessible, and were made possible thanks to a recently completed research project of the Swiss National Science Foundation at the Bern University of the Arts reappraised. The activities of the STV as well as its functioning point to developments, continuities and breaks. Today, eight years after its dissolution, the club's history can be read from the back. What brought STV to its downfall after 117 years of functioning? Did it successfully make itself redundant or have times simply changed?

When the STV celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1975, it was at the height of its national reputation. The fact that the long-serving Honorary President Paul Sacher sounded out whether the Federal Council in corpore The self-assessment shows that the company would not be invited. Nevertheless, Federal Councillor Hans Hürlimann gave a speech, promised more subsidies and also wrote a contribution to the commemorative publication.

Failed reforms and internal strife

President Klaus Huber brought movement to this time-honored association. Initially, he initiated many reforms. The Tonkünstlerfest 1982 in Zofingen was a first, albeit clumsy, attempt to soften aesthetic fronts and integrate improvised music. The increased participation of women and foreigners was important to Huber. However, he was so tactically inept in the implementation that both failed for the time being. The sixty-eight-year-old saw all of this as a contribution to participation. But his conduct of meetings was time-consuming. A lack of availability and disloyal behavior led to conflicts, which Honorary President Sacher tried to settle in a court of arbitration. Hans Ulrich Lehmann said that Huber wanted to be democratic, but was authoritarian, and Jean Balissat said: "Our President has a strong personality, but this is hardly transferable to the office of President." (1)

Eric Gaudibert was shocked by Huber's unauthorized leave of absence, which revealed contempt and egocentricity as well as a breach of ethics. Urs Frauchiger denied him any suitability for the office: "A president must be a manager, have organizational skills and time at his disposal. He therefore asked him to resign from office." (2) In his last presidential address, Huber took stock of the situation: The STV was in "urgent need of renewal". He identified a "trench instinct" and warned against a "secession".

Dissonance and a breath of fresh air

The following president, Jean Balissat, also caused glaring disharmony with a targeted attack. At the 1986 Tonkünstlerfest in Fribourg, where Balissat also enjoyed a high social status as conductor of the official brass band, the association magazine Dissonance a reckoning by Jürg Stenzl. A re-reading of the polemic and its accompanying documents shows superficially the regret of a musicologist who sees himself as progressive in the face of an allegedly regressive development of the composer. However, the criticism of a short piano piece reveals the whole malaise: unease at the accumulation of power and disdain for contemporary music from the Suisse romande.

The conflict drove a wedge between the cultures of German-speaking and French-speaking Switzerland. The storm in a teacup turned into an uprising of the young against the authorities, of the avant-gardists against the traditionalists. Above all, a different understanding of the task of music criticism became apparent. While Stenzl in the Swiss Music Newspaper lines such as those between traditionalists and avant-gardists and between western and German-speaking Swiss, Keller took up the Dissonance The magazine anticipated the debate: the emancipation of women, the perception of improvisation, the reappraisal of the association's past. This defiant attitude earned the magazine the disparaging title of "party organ".

A new wind was blowing under Daniel Fueter. The new beginning was staged programmatically: For the federal jubilee year 1991, Fueter outlined a utopia inspired by the national poet Gottfried Keller: "At last, we could dream of culturally interested, lateral-minded state writers or publicly funded, politically active artists who deal with current creative work within and beyond the country's borders." The fact that Fueter drafted this manifesto in the very year that Switzerland was reflecting on itself was explosive and heralded the further opening of the association to improvisation, women and foreigners, who were now integrated into the festival for the first time.

Composer prizes as aesthetic guidelines

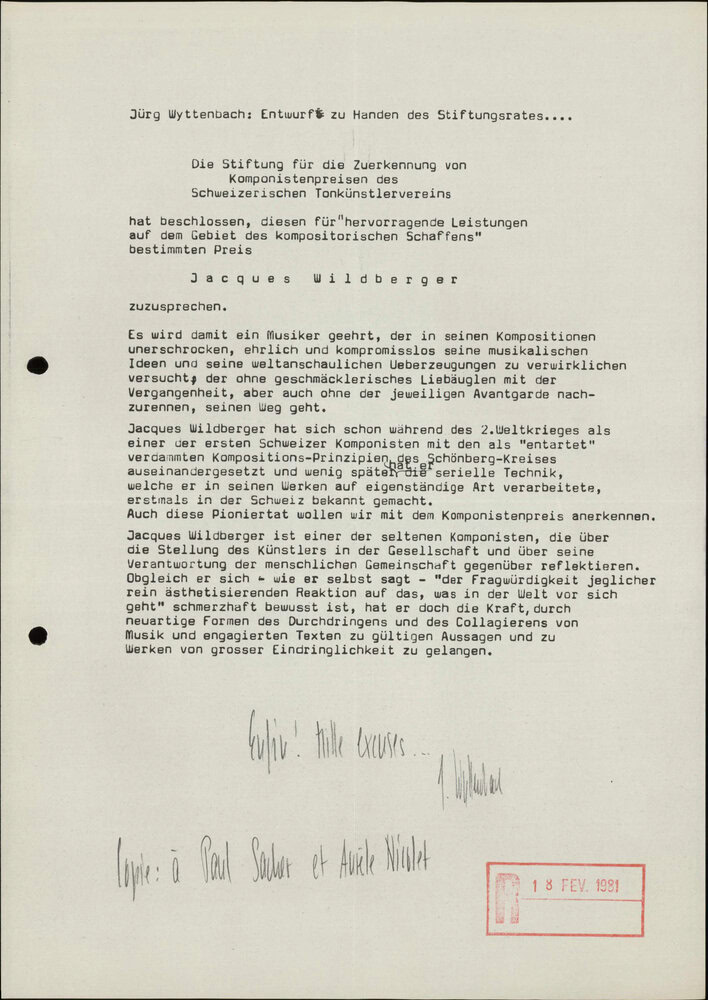

The composers' prizes were highly prestigious. Their dignified presentation reflected the STV's self-image. The slow change in discourse over the years can be seen above all in the awards. In the beginning, traditional and national values were emphasized, and supposedly typically Swiss qualities such as masterful craftsmanship were stressed. In the post-war period, a deliberate discourse of differentiation from the avant-garde can be observed in awards and the selection of award winners that tended to look backwards. It was only later that criteria such as innovation, originality, internationality and communication skills became important.

As late as 1981, Jürg Wyttenbach's laudatory speech for Jacques Wildberger caused a stir with jury president Paul Sacher because of its unusual political tone: "On a second reading, I am disturbed by the 2nd paragraph, 3rd line: 'condemned as degenerate'. As National Socialism fortunately never came to power in Switzerland, we should not quote it here either. I would therefore ask you to delete these three words. I also don't particularly like the beginning of the third paragraph on a second reading. I think there are still a great many composers who think about the position of the artist in society!"

The conflict arose years later: names were discussed, Rolf Liebermann and Peter Mieg, who were immediately eliminated, as well as Armin Schibler and Julien-François Zbinden: "Mr. Sacher is of the opinion that both should receive the prize in 1987." (3) Aurèle Nicolet objected and demanded that no one be honored - or else Hans Ulrich Lehmann. The decision was postponed. Sacher probably sensed that his influence was waning. He made a compromise and dropped Schibler, who had since died, in favor of Lehmann: "Gentlemen, you know that a malaise is spreading in French-speaking Switzerland. Small gestures in intellectual and artistic circles are particularly noticed. For these reasons, I would like to return to our decision and urge you to award our prize this year to Mr. Lehmann and Mr. Zbinden. In doing so, I would like to make an attempt to contribute to the improvement between French- and German-speaking Switzerland."

To emphasize how important this was to him, Nicolet wrote a detailed letter on his tour of Norway, playing on his rhetorical skills and charming empathy to ensure that Gaudibert (and Lehmann) were awarded the prize instead of Zbinden: "Of course, like everyone else, I feel the musical malaise in Switzerland. [...]. This malaise is also not the 'exclusive' Switzerland's privilege, but it is necessarily felt more deeply in a country that is neither willing nor able to question itself and only clings to the values of the past. This guarantees it material prosperity, but increasingly isolates it spiritually and culturally from the rest of Europe and the world. To come back to the problem you mentioned, I very much doubt that the awarding of the STV prize to J. F. Zbinden will in any way ease the situation of Swiss music in general and that of the STV in particular. Do you want to put up both the goat and the cabbage? That's a reflexive attitude that is not justified in our 'good old' country was learned and acquired. If it is right to choose a Romand, I will give my vote to E. Gaudibert. But a Lehmann-Zbinden ticket only seems to me to document our confusion, whereas the choice of the Lehmann-Gaudibert tandem expresses a taste and an attachment to musical values that we want to defend and promote."

Balance and culture shocks

The STV endeavored to maintain the fragile balance between the language cultures and promote mutual interest. Presidents changed in rotation, there was guaranteed minority representation on the board, and attempts were made to strike a balance in the magazine, festivals and CDs. According to former President Nicolas Bolens, there were hardly any conflicts: "There was certainly an unease that we all felt. It was more at the level of the functioning of the board than at the level of aesthetics." He felt that bringing people together was an important task: "The positions could be very different, but it's also about learning respect. The ways of thinking and working are not the same, which forced us into a dialog, into cultural encounters. Cultural encounters, yes, cultural shocks, which these festivals were, which the STV made possible. And I think that's important for national cohesion. That's what makes the moments of dialog, of encounter."

Foreigners, women and improvisers as minorities

Foreign composers and musicians were initially treated on an equal footing with their Swiss colleagues. In a broad arc, there were then increasing tendencies towards exclusion in a changing political context, but also due to fear of competition, until the last few decades saw a gradual reopening. Protectionism and later integration took place in autonomous succession, partly in parallel with the political amendment of laws, partly delayed.

According to the statutes, women had equal rights, de facto However, they were largely kept away from power, honor and pots of money for a long time. Here, too, the development took place parallel to the emancipation of the state. However, denial or non-recognition of the gender imbalance can still be observed in recent times. All the more important are the personalities who drove these developments forward, from the appointment of board members to the handling of applications, selections and specific topics.

Improvisers were also excluded for a long time. It was only in tentative steps that they were recognized and taken into account, having previously not been taken seriously due to a lack of professional training or measured against inappropriate criteria. The controversy surrounding a negatively received article by Thomas Meyer in Dissonancewho ultimately gave the improv scene a new impetus - not least at Pro Helvetia, where Meyer, who was under attack, was a member of the Board of Trustees.

Sound carrier production with unclear objectives

Even if the purpose of the self-produced recordings was never explicitly defined, certain intentions can be read from the actual practice: The aim was to document contemporary musical life in Switzerland. For the composers and performers represented, it was a calling card, an honor and a PR tool. Swiss radio stations were able to fulfill their cultural mandate, while foreign stations were able to satisfy musical curiosity and the need for information. Alluding to previous practices, Pierre Sublet posed the fundamental question: "Do we want to launch someone or make someone happy, do we want something more representative?", to which Roman Brotbeck responded with his own radicalism: "You have to ask yourself what you would like to hear in New York, for example."

Saved to death or survived?

In 2017, the Federal Office of Culture cut the subsidies for the STV. As a result, it merged with other associations to form the professional association Sonart. At first glance, the reasons seem clear: political pressure and financial bleeding. However, an examination of the association's documents combined with interviews with contemporary witnesses shows that the end had a variety of causes and was announced early on: expensive association structures, an opening up of content as a culture of outsourcing, whereby the sovereignty of discourse was relinquished. The context was neglected: the STV had become one of many players. Its significance faded; contemporary music organizers were now to be found all over Switzerland. The Tonkünstlerfest was absorbed into other festivals, which more than made up for the absence of its own audience, but its unique profile disappeared.

The same applied to the CD series, which the orchestra was less and less able to shape itself and eventually gave up, along with many other activities from soloist to composer prizes, from writing residencies in the Ticino working residence Carona to the musicians' agenda. The core of the former profile was lost and older members were scared away. For a long time, it insisted on its cultural mission and neglected the understanding of service required by the federal government.

Did this disappearance mean a negligent or even willful destruction of musical structure? Looking back, only an ambivalent answer is possible. They excluded themselves, were also a little arrogant about it, they were preoccupied with themselves for too long, and although they were aware of the political weather light, they didn't react enough and tactically missed opportunities. But the end can also be interpreted positively: The STV has successfully fulfilled its mission. It has made itself superfluous because the situation has changed. And it survived itself in new services, which were extremely important during the Covid crisis, offered by the successor organization Sonart, in cultural activities that were taken up elsewhere, and in the collective memory, numerous documents and reflection on them.

__________

Notes:

(1) Minutes of the extraordinary meeting of the STV Board of Directors on January 18, 1981, pp. 2-6.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Minutes of the meeting of the Board of Trustees on February 2, 1986, p. 1.

__________

As part of the Lucerne Festival Forward, events on STV will take place on November 22 and 23 at the Kultur- und Kongresshaus KKL: An exhibition, a panel discussion and the vernissage (Nov. 22, 4 p.m.) of two anthologies :

- At the center of developments. The Swiss Association of Musicians 1975-2017, ed. by Thomas Gartmann and Doris Lanz, Zurich: Chronos 2025.

- Music discourses after 1970ed. by Thomas Gartmann, Doris Lanz, Raphaël Sudan and Gabrielle Weber, with editorial assistance from Daniel Allenbach, Musikforschung der Hochschule der Künste Bern, vol. 19, Baden-Baden: Ergon 2025.

Thomas Gartmann led the SNSF project on STV at the Bern University of the Arts, where he is responsible for research.