The gender of power

On the 400th anniversary of his death, Shakespeare is everywhere. As in Basel and Zurich, new productions of Verdi's "Macbeth" are therefore booming. An occasion for an examination of gender roles in this opera, which leaves the cliché of the destruction of terminally ill women in Verdi operas far behind.

The key passage is found in the middle of the opera. In the supernatural, spectacular third act, the last in a series of silent ghosts of past kings, the army commander Banco appears. Killed by him and never king himself, he holds up the mirror of power to Macbeth with a grin: Banco sees in him not only himself, but the extension of himself into the future; the continuation of his power in his descendants. The glass does not reflect the outer body, but refers to the ruling body, which exists independently of physical presence. If Macbeth were to look in the mirror, he would remain blind: the childless murderer would see himself without a future, his deeds would be condemned to transience, his power to destruction.

Inside view and outside view

In Banco's mirror, the course of the plot is also reversed, with the build-up of power turning into a decline in power. But the opera is also characterized by the view into the mirror, because the central question is: what is visible on the outside, what remains an inner view, what is "real", what is "delusion". This refers not only to sounds - such as the bell that seems to incite Macbeth to commit murder, or the voices of the witches and ghosts - but also to visibility: Who actually sees them, the ghosts of the murdered, the blood on the hands of the murderers and, last but not least, the first protagonists of the opera, the witches:

"Who are you? From this world

or other spheres?

I am forbidden to call you women

your dirty beard."

These words by Banco already make it clear at the beginning that the power of the witches also lies in their intersexuality, which emphasizes their otherworldliness. Lady Macbeth also stands between the sexes, whose thirst for power makes her look contemptuously at her initially hesitant husband and his feelings of guilt. And this role is also reversed in Banco's mirror: after looking into the future, Macbeth is unscrupulously confident of victory and the Lady perishes from her feelings of guilt in a sleepwalking delusion. As Freud has already described in Shakespeare, the couple appears as a complementary unit with flexible gender role attributions.

Disappeared in the black or overly clear

Barrie Kosky in Zurich and Olivier Py in Basel decide how to deal with the central question of visibility in the scenic realization in completely contrasting ways. With Kosky's bold statement that he is "fed up with set theater", the Zurich production restricts itself to a pure interior view, to disembodiment.

The main characters are dressed in almost gender-neutral black medieval robes and act in a cone of light. The rest disappear into the blackness of inner abysses: The feast, the ghosts and apparitions are relegated to the characters' heads and hearts, and even Banco and his mirror remain disembodied and yet powerful-voiced. They also gain a ghostly presence through acoustic and visual distortion. And it works - not least because of the magnificent musical design, especially in the last two acts, under the direction of Teodor Currentzis, who knows how to create eternal arcs of tension and displays an earthy musicality.

In contrast, the Basel approach takes us right into the middle of a kind of fascist Halloween, in which the horror becomes abundantly clear: every outrage and every supernatural act is presented in detail - even the crime against King Duncan, which has mutated into a bathtub murder and was banished backstage by Verdi, and the piles of corpses in the dictatorship's backyard. In Olivier Py's film-noir aesthetic, Banco's oversized standing mirror remains blinded by age spots: It does not serve Macbeth as a reflection of himself, but rather oversized images of power (statue and portrait) created during the rarely performed ballet music - which eventually fall to the ground noisily and accompanied by lightning.

The intersexuality of witches

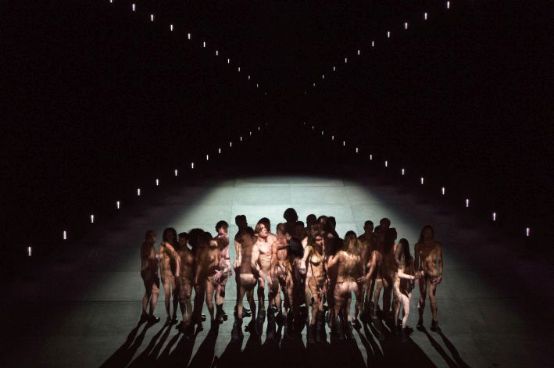

What remains astonishing is that the solution to the "witch problem" is the same in both productions despite these fundamentally different directorial approaches: both directors have opted for a separation of singing witches and nude extras. In Zurich, gender is only clearly referenced visually and thus physically in the case of the intersex witches: Extras show hermaphroditic bodies with breasts and penises in flickering electronic light waves, while the singing witches' choir remains invisible in black on both sides of the stage. In Basel, the singers, who remain visible as a black moving choir, are accompanied by undressed women and men - as a visualization of both sexes, also detached from the singers, but in separate bodies.

Both productions thus find convincing ways to unite the musical contrasts of the witches' appearances, which are not unproblematic for today's productions: dancing, frivolous lightness is juxtaposed with prophetically impressive depth of soul in the prophecies. By creating spaces for visible intersexuality through pronounced inwardness (as in Zurich) or by questioning gender roles and voices through a new combination of sound and image rooted in the supernatural (as in Basel) - both production approaches urgently encourage an expansion of the view of gender roles in Verdi operas: It is about far more than the annihilation of deathly beautiful singing women in the role of victim. Especially when Shakespeare, with the gender theory of his time in the background, is the godfather.