AI recognizes Mozart's facial features

Modern technology sheds light on the authenticity of historical portraits. Biometric facial recognition reveals whether Mozart is actually depicted in a Mozart painting.

I start my laptop to write this article. Soon the two red camera eyes are flashing and checking my identity. They compare a stored image of me with what they are currently recording. No matter what glasses I'm wearing, whether I've had my hair cut or have a scar on my face from shaving, there's nothing to confuse the biometric facial recognition system, nothing to stop it from recognizing my identity.

When depositing the original image, this technology measured the distances between around thirty points of the facial landscape. These include key factors such as the distance between the eyes, the distance between the forehead and the chin, the shape of the cheekbones and the contours of the lips, ears and chin. All this data was then converted into a mathematical formula, a numerical code, and stored. Just like a fingerprint, the resulting "face print" is unique to each person.

What did Mozart look like?

The portraits of this unique genius are countless: real, fake, attributed, lost and rediscovered, dubious and unambiguous, artistically valuable and less valuable. And new ones are constantly being found. These then either lead to a huge flurry of articles in the media, or they are barely noticed.

There are a handful of portraits that are written about in detail in the Mozart family letters and their resemblance to the son or brother is reported. But what did Mozart (1756-1791) really look like, which one is the "real" Mozart? Many a fierce dispute has broken out among music scholars about this. Now, however, biometric facial recognition is available as an aid that seems likely to make the disputes more objective.

Since the beginning of the new millennium, the method, which was invented in Japan in 1980, has rapidly gained momentum and, as one of the many AI functions, it is hard to imagine life today without it. It is hardly surprising that it has also begun to occupy modern musicology, albeit cautiously and with a great deal of skepticism. Here are two concrete examples of how it can be used to verify the authenticity of Mozart portraits.

A new "last" portrait

Until 2002, the depot holdings of the Berlin Gemäldegalerie contained a collection entitled Gentleman in the green skirt an oil painting by the Munich painter Georg Edlinger (1741-1819). It was painted in 1790, one year before Mozart's death.1

As early as 1995, a certain resemblance to the so-called Bologna portrait of 1777, which Leopold Mozart had painted by his 21-year-old son and sent to the Academy in Bologna for its gallery, was thought to have been discovered (collage top row, 4th from left; bottom row, 2nd from right). He praised it as particularly apt.

In 2006, Rainer Michaelis, the chief curator of the Berlin Gemäldegalerie, together with the Swedish neurobiologist Martin Braun, undertook a highly interesting attempt to compare the two paintings using the latest biometric-statistical methods. 2

The astonishing result was that the Edlinger portrait shows the same person as the Bologna portrait with a probability of 1:10,000,000.3 This makes the Edlinger portrait the last Mozart portrait painted during his lifetime. As early as 2006, the Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen Berlin published a carefully edited and excellently illustrated special edition in its "Bilder im Blickpunkt" series.4

A youth portrait?

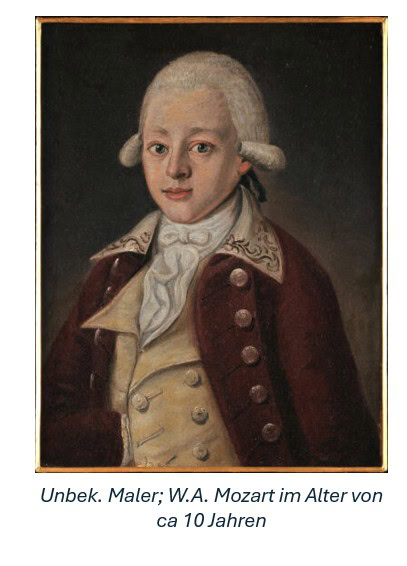

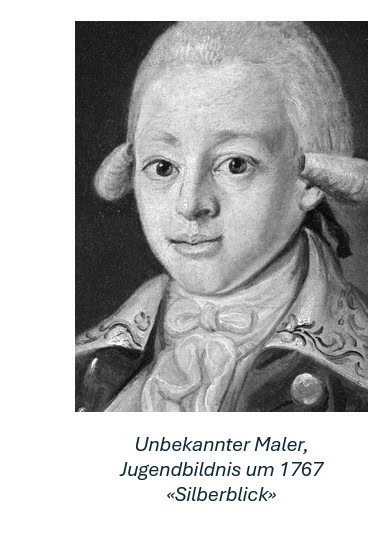

Not far from Salzburg, a professor emeritus from the University of Constance, who goes by the pseudonym "Bilddetektiv"5 In an art shop, he came across a rather inconspicuous picture of a young man that immediately fascinated him: Somehow this open face of the young man seemed familiar to him. The picture detective had been studying artists' portraits and the physiognomic authenticity of the sitters for a long time. In over thirty works, he had acquired an enormous amount of knowledge about painting techniques, biographical and historical backgrounds and contexts and had honed his powers of observation for the smallest physiognomic and physiological details. After making comparisons with known Mozart paintings, it was clear to him that the portrait found at the time could well depict Mozart at the age of around ten.

The picture detective was well aware that "new" Mozart portraits continue to appear to this day, but that they cannot be verified. He therefore proceeded with caution. He initially substantiated his thesis that the portrait he had found depicted the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart by comparing it with the portraits of Joseph Lange, Dorothea Stock and Joseph Grassi, which were considered authentic, and with the one by Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni from 1763, which shows the child Mozart at the age of six (collage, bottom row, 3rd from right). He primarily relied on the comparative observation of physiognomic features.

The picture detective was well aware that "new" Mozart portraits continue to appear to this day, but that they cannot be verified. He therefore proceeded with caution. He initially substantiated his thesis that the portrait he had found depicted the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart by comparing it with the portraits of Joseph Lange, Dorothea Stock and Joseph Grassi, which were considered authentic, and with the one by Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni from 1763, which shows the child Mozart at the age of six (collage, bottom row, 3rd from right). He primarily relied on the comparative observation of physiognomic features.

The research results showed that the size "and shape of the head (forehead, temple, face shape) are the same in all images, as are the distance between the eyes and the proportions of the face. The soft tissues may change in the course of life, but the skull remains the same."

The picture detective also points out another important feature for identifying the sitter, which Eva Gesine Baur describes in her book Mozart, genius and Eros has noted.7 In the caption to a portrait of Mozart shown there, she writes: "Here too, inward strabismus, the squinting inwards (of the right eye), is visible, according to ophthalmology often the result of serious illnesses in the first years of life. It is documented in Wolfgang's case for the year 1767 (smallpox epidemic). This would explain why he is not squinting in the Lorenzoni portrait of 1763." He confirms that the squint in the right eye mentioned by Baur can also be seen in the present youth portrait: "The misalignment of the eyes is a key biometric feature with a prevalence of less than 3 percent. This significantly reduces the probability of random parallelism (less than p of 0.03 in the binomial model)."

In order to verify the assumptions based purely on observation, the portrait was finally examined using biometric facial recognition in comparison with the four paintings mentioned above. The aim was to prove that the picture did not depict Mozart.

In order to verify the assumptions based purely on observation, the portrait was finally examined using biometric facial recognition in comparison with the four paintings mentioned above. The aim was to prove that the picture did not depict Mozart.

In summary, the image detective concludes: "The probability of a match is between 82 and < 85 percent, depending on the question. There is a very high match in the invariant facial features: Eye position, eye color, eyebrow shape, lip and chin shape as well as in the clothing and hairstyle-specific typology of the late 1760s. The average linear deviation in the distance between the eyes and the Grassi oil portrait is only 3.7 percent of the bipupillary distance and is therefore below the typical 5 percent threshold, which is considered an 'identical resemblance' in forensic image anthropology. Minor discrepancies (e.g. underdeveloped nasal length of the child or rounder cheeks) can be explained by ontogenetic growth processes and do not contradict the identity. The nose grows postpubertally by approx. 1.3 mm/year (anthropometric longitudinal data). A child portrayed at the age of 7.8 years therefore has a significantly shorter nasal bridge than the 26-year-old adult."

It was therefore not possible to support the hypothesis that the portrait does not depict Mozart (Popper's falsification criterion).

Conclusion

The iconography (image description) of the visual representations of sound artists is an extraordinarily broad field: musicology and art studies, psychology, sociology, medicine, neurobiology, style and costume studies all overlap here.

It may come as a surprise that all of the above-mentioned disciplines were involved in the research on Edlinger's Berlin painting ("Man in a Green Skirt", Mozart) and the newly discovered youth portrait, but musicology was unfortunately absent! Yet it can be assumed that the cooperation of all specialists would be of the greatest common benefit. For example, biometric facial recognition could be used as a starting point or as conclusive evidence for controversial questions of identity. In the case of Mozart, for example, this would be the question of whether Mozart is really depicted in the very popular Verona picture or in the strange portrait of Josef Hickel:

These questions should also be able to be answered objectively and conclusively in close cooperation with all the disciplines involved and with the aid of in-depth biometric investigations.

Notes

1 On Mozart's life situation at the end of October 1790, see Ueli Ganz on https://mozartweg.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Wie-Mozart-nicht-aussah.pdf

2 To the Michaelis/Braun report on procedure and conclusions http://www.neuroscience-of-music.se/ormen/Edlinger%20Mozart.htm

3 https://dieterdavidscholz.de/ausstellungen/j-g-edlingers-letztes-mozart-bildnis.html

4 Michaelis Rainer, The Mozart portrait in the Berlin Picture GalleryPreussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin 2006, ISBN-13: 9783886095292

5 The author of this article (UG) knows the full name of the picture detective.

6 Available on: https://bilddetek.hypotheses.org/2096

7 Eva Gesine Baur: Mozart, Genius and Eros - A Biography C.H.Beck, 2014; (to the legend of the endpaper before page 86 VI/1771)