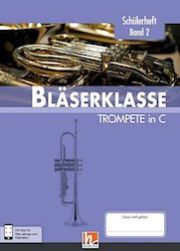

The teacher's handbook for the new teaching aid from the publisher Helbling Wind class guide comes with the weighty volume of more than 450 densely printed pages. The textbook impresses with a wealth of extremely varied and stimulating material. In addition to the teacher's book, it includes student booklets for all wind orchestra instruments, play-alongs and online aids that can be accessed via a code, as well as a CD-ROM with a wealth of additional material.

The Wind class guide was jointly developed by five authors, all of whom teach music at secondary school level and have experience in working with wind classes as well as in school music. The aim of the new teaching aid is to combine the playing practice that dominates wind band classes today with the content of school music lessons (music theory, ear training, creating and inventing music). The teaching material is not aimed at a specific age group. It is suitable for use from intermediate level upwards. The teacher's book explains the concept, the underlying ideas and objectives as well as the methods used in the work with the classes in detail.

The teaching part begins with a preliminary course, which takes place without instruments and extends over 3 units, i.e. approx. 6 lessons. This is followed by Basics with instrumental methodology and then the lessons with the instrument, which are divided into two volumes with 23 and 18 lessons respectively (1st/2nd volume). Each lesson offers material and fully prepared lesson plans for 2 lessons.

This concept is based on 3 lessons of extended music lessons per week, divided into 2 lessons of regular music lessons with the whole class and 1 lesson of instrumental lessons in small groups. If less teaching time is available, it may be difficult to complete the two volumes within 2 school years.

In terms of content, the teaching material places great emphasis on teaching music theory. The basics are introduced thoroughly, but also in an extremely varied and playful way, with lots of suggestions for partner or group work. At the same time, the theoretical content is linked to practical playing on the instrument and used for creative tasks. Pupils are always encouraged to engage in practical activities. On average, there are one or two short pieces of music per lesson (chapter), which is rather few. In most cases, the pieces are accompanied by additional suggestions for interpretation, presentation or reflection as well as links to theory. For many pieces, additional four-part class arrangements with a 2nd part, a bass part and an upper part "for experienced players" are available on the accompanying CD-ROM, which allows for individualization of the requirements through internal differentiation.

Using specially marked toolboxes, the pupils are taught specific methods as a craft, how they can work on music independently, practise pieces or acquire musical material. The student booklets are attractively designed with colors and symbols and contain supportive and stimulating pictures and graphics. However, the pages as a whole seem rather overloaded and very text-heavy, which makes accessibility somewhat more difficult.

Wind class guide sets new standards in terms of thematic breadth, the teaching of theory and a general understanding of music, as well as in its methodical and didactic preparation.

Sommer/Ernst/Holzinger/Jandl/Scheider: Leitfaden Bläserklasse. A concept for successful teaching with wind instruments, teacher's volume 1 and 2 incl. CD-ROM and pupils' solution booklets, S7770, Fr. 84.50, Helbling, Belp et al.