Friends on both sides of the Iron Curtain

Meinhard Saremba traces the artistic friendship between Britten and Shostakovich in his book.

The venture was worthwhile to bring the two composers out of the shadows of politics, the English composer Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) in the time of the decline of a world empire, and the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) in the terrifying Soviet era. Their acquaintance, which came about rather by chance in 1960 and developed into a friendship across the almost insurmountable border of the Cold War, is portrayed in the most diverse facets of artistic and human relationships. Despite all the adversity, they were able to meet six times, both in Aldeburgh and Moscow and on their joint trip to Armenia (summer 1965).

The author endeavors to incorporate major political events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact states in 1968 and the heated discussion in Great Britain about the 1972 festival of Soviet music into the debates about the development of New Music, without neglecting the focus on the two artists as threatened existences. For from this point of view, they were judged as composers in a completely controversial manner before and after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the discussions in East and West continue unabated today, as both could hardly ever be counted among the avant-garde and their works were therefore often judged and condemned below their worth.

An overabundance of quotations from English and Russian sources - listed in well over a thousand annotations - often replace an opinion expected from the author. His primary concern, however, is not to reassess the works, but to shed new light on the sometimes comparably difficult circumstances under which the works were composed. Since both composers had to deal with the political events and thus often, but not always, became unintentionally involved, this required extensive research into their private lives. The "Changing Meanings of Values and Words" or details of the cultural exchange agreement between Great Britain and the USSR in 1959 go far beyond this, but often provide an insight into forgotten events during the Cold War.

However, such overviews harbor the danger that the geopolitical aspects, understood from a narrow cultural perspective, do not always stand up to an overall historical assessment. On the other hand, it is commendable that the author also attempts to shed light on the problematic aspects of the individualists who were forced into outsider roles.

Meinhard Saremba: Keeping the cultural door open. Britten and Shostakovich. Eine Künstlerfreundschaft im Schatten der Politik, 518 p., € 28.00, Osburg-Verlag Hamburg, Eimsbüttel 2022, ISBN 978-3-95510-295-1

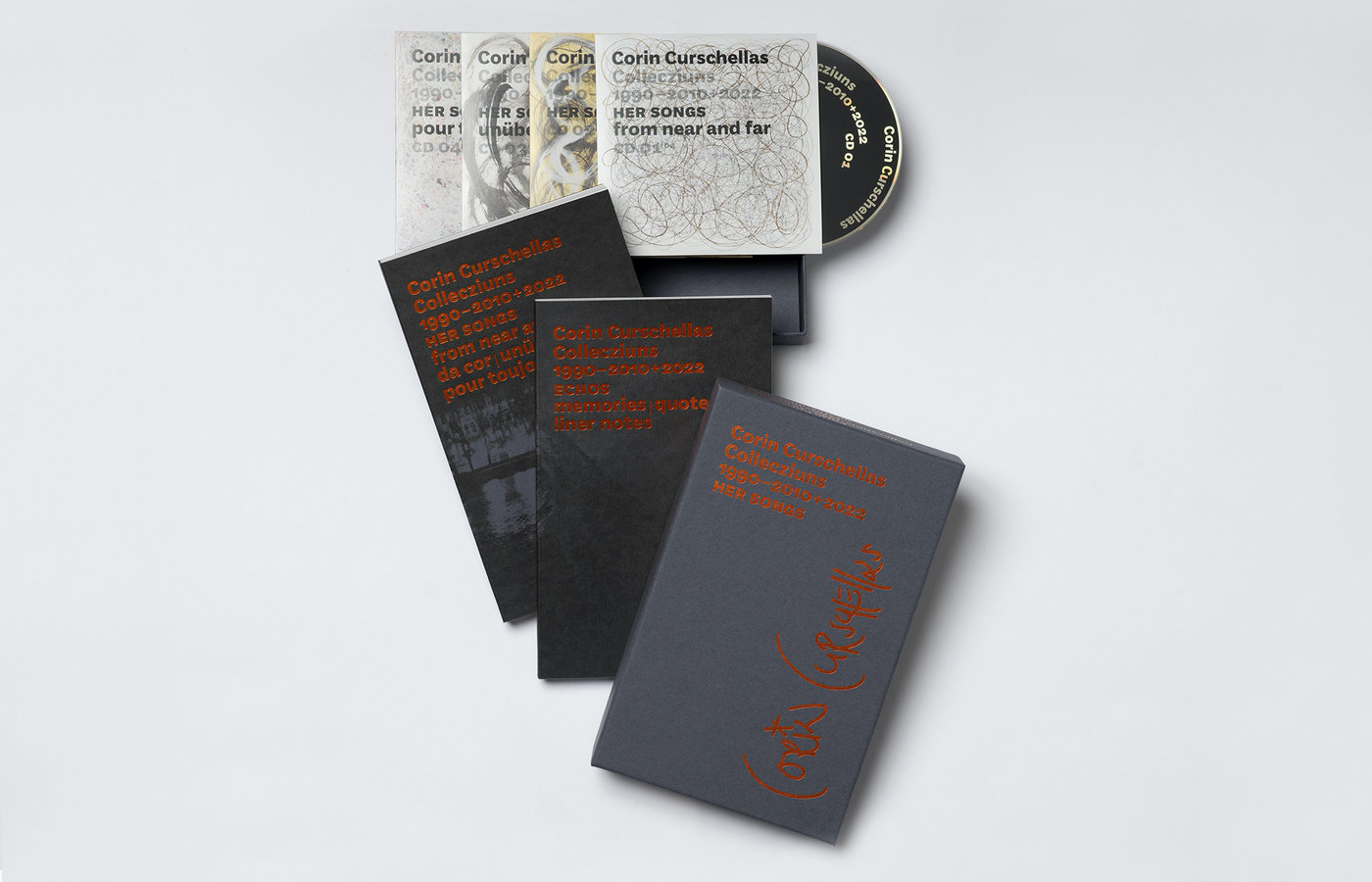

Corin Curschellas: Collecziuns 1990-2010 + 2022 Her Songs, Tourbo Music TOURBO068

Corin Curschellas: Collecziuns 1990-2010 + 2022 Her Songs, Tourbo Music TOURBO068

Euday Bowman: Three Ragtimes for Clarinet and Piano, arranged by Heinz Bethmann, BU 6244, € 15.00, Bruno Uetz Musikverlag, Halberstadt

Euday Bowman: Three Ragtimes for Clarinet and Piano, arranged by Heinz Bethmann, BU 6244, € 15.00, Bruno Uetz Musikverlag, Halberstadt

Makhdoomis Catching Moments on the other hand, is a contemporary, traditionally notated composition divided into three sections and entitled "mystical, free". The beginning and end have an improvisatory character and are reminiscent of Indian flute music. Again and again, the music lingers on longer notes in order to move towards a pause or the next long note in short, fast runs or rhythmic sequences. The rhythmic, faster middle section is intended to be rhetorical, beginning with noisy and precisely notated syllables to be spoken into the flute and then discharging into multiphonics and audible finger clacking.

Makhdoomis Catching Moments on the other hand, is a contemporary, traditionally notated composition divided into three sections and entitled "mystical, free". The beginning and end have an improvisatory character and are reminiscent of Indian flute music. Again and again, the music lingers on longer notes in order to move towards a pause or the next long note in short, fast runs or rhythmic sequences. The rhythmic, faster middle section is intended to be rhetorical, beginning with noisy and precisely notated syllables to be spoken into the flute and then discharging into multiphonics and audible finger clacking. Isaac Makhdoomi cannot be easily pigeonholed as a performer either. He has been known to television audiences since his appearance on "Switzerland's Greatest Talents" as part of the band Sangit Saathi, where he elicited funky sounds from the recorder and delighted the audience. His newly released CD with the concerti by Antonio Vivaldi shows a completely different side of the musician. The cleverly conceived and exceptionally beautifully mixed album, in which Makhdoomi juxtaposes the well-known concerti with two aria jewels, impresses not only with its powerful virtuosity, clearly contoured dynamics, exciting instrumentation in the continuo and improvisatory moments, but above all with its great individuality and longing for sound in the lyrical and richly ornamented slow movements.

Isaac Makhdoomi cannot be easily pigeonholed as a performer either. He has been known to television audiences since his appearance on "Switzerland's Greatest Talents" as part of the band Sangit Saathi, where he elicited funky sounds from the recorder and delighted the audience. His newly released CD with the concerti by Antonio Vivaldi shows a completely different side of the musician. The cleverly conceived and exceptionally beautifully mixed album, in which Makhdoomi juxtaposes the well-known concerti with two aria jewels, impresses not only with its powerful virtuosity, clearly contoured dynamics, exciting instrumentation in the continuo and improvisatory moments, but above all with its great individuality and longing for sound in the lyrical and richly ornamented slow movements.

Joachim Raff: Six Morceaux for violin and piano op. 85, edited by Stefan Kägi and Severin Kolb, EB 9407, € 28.50, Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden

Joachim Raff: Six Morceaux for violin and piano op. 85, edited by Stefan Kägi and Severin Kolb, EB 9407, € 28.50, Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden

Carl Friedrich Abel: Cello Concerto No. 2 in C major, WKO 60, edited by Markus Möllenbeck, piano reduction, EW1112, € 24.80, Edition Walhall, Magdeburg

Carl Friedrich Abel: Cello Concerto No. 2 in C major, WKO 60, edited by Markus Möllenbeck, piano reduction, EW1112, € 24.80, Edition Walhall, Magdeburg