The National Sound Archives between past and future

Founded in 1987 in Lugano and now part of the National Library, the Phonotheque collects, preserves and makes accessible Switzerland's audio cultural heritage. It takes care of all public and private recordings with documentary or identity-forming value for the country: music, voices, interviews, advertising or soundscapes.

It's a gesture from childhood and, depending on our romantic disposition, we don't stop doing it later. Don't you sometimes hold one of those shells on the bookshelf to your ear? «Listen to the sea», we were told when we were little, because it's well known: Seashells have the magical ability to soak up the sound of their surroundings and retain it forever. Later we learned (if we wanted to) that they are only small, imperfect resonating bodies for the surrounding sounds, including our blood pulsing through our ears. But the desire to believe in this small sea remains. It probably corresponds to the great desire of our species to appropriate what surrounds it in the most intangible and fleeting form, the world of sound.

Sound waves, which make up everything audible, spread out and eventually disappear. The idea of repeating a sequence of musical notes or words identically proves to be a chimera. Musicians and actresses experience this time and again. To mitigate this loss of control, man invented the technique of writing. Verba volant, scripta manent: an ingenious remedy for the constant loss of energy in the world of sound. Writing is an encryption that is not aimed at preservation, but at the repeatability of what is meant, relying on the imagination of the human brain.

But what about the true sound, the true object? The castrati of baroque Rome practiced in front of reverberating walls to catch a fleeting echo of their voice, and it was not until 1857 that Éduard Léon Scott de Martinville patented the phonautograph, a kind of oscillometer with which he could record sound waves on blackened glass. Recording, but not yet reproducing. It was not until 2008 that his phonautograms were made audible: a fragment from Au Clair de la Lune, some verses from Tasso and other small experiments.

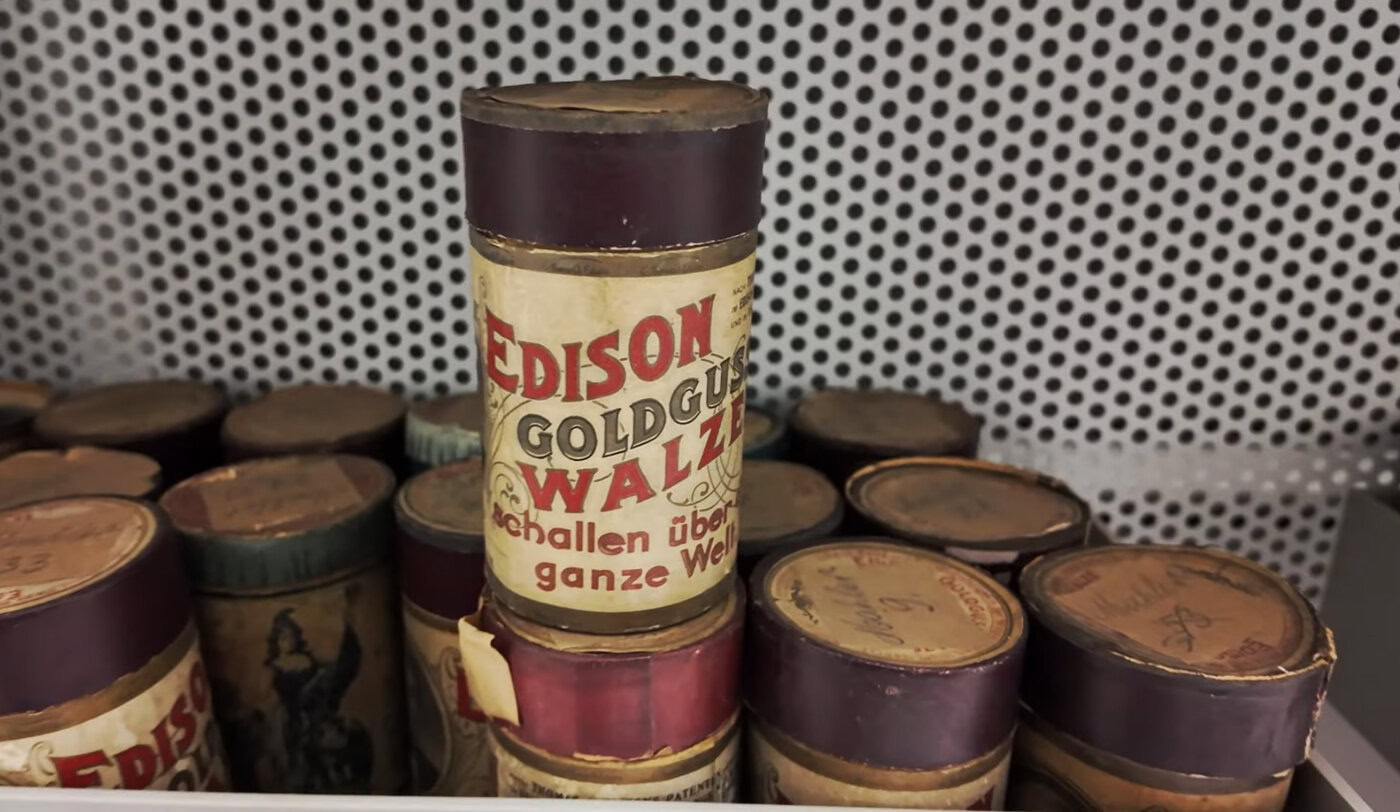

In 1878, Edison patented his phonograph, in which the vibrations from a needle were scratched onto a foil-covered cylinder and which now also made the reverse possible: to «read» the groove again, to hear what had been recorded. In 1888, Berliner used records instead of cylinders, which were more suitable for mass production and marketing. The 20th century then saw the transition to electrical recordings on magnetic tapes and finally to purely digital recordings and the final dematerialization of the sound carrier: music moved to the internet. Today, we can use our smartphones to make and play back recordings for hours on end and access almost all of the world's music online.

A library of sounds

Libraries exist to preserve written documents and make them available to the public. And for sounds? If sounds can be recorded, the question arises as to what should happen to the carriers of these sounding memories of a society.

Already at the end of the 19th century, a few years after Edison's invention, there was an eagerness to record. Some European institutions recognized early on that it was just as important to preserve this heritage as written records. Thus the Vienna Phonogram Archive was founded in 1899 and the Berlin Phonogram Archive in 1900. In Switzerland, the National Library has also been collecting some sound documents since the beginning of the last century. In the 1960s, however, there was a call for a specialized institution. In 1984, the municipality of Lugano provided premises and funds, which led to the establishment of the National Sound Archives Foundation in 1987. In 2016, it became a section of the National Library. After starting out in Studio Foce, the Phonotheque moved to the Centro San Carlo in 2000. In 2031, it will move to the Città della Musica, a futuristic project that will bring together various partners from the music sector in the premises of Radio RSI in Besso.

The mission of the Swiss National Sound Archives is derived from the Federal Act on the Swiss National Library: to collect, catalog, preserve, make accessible and publicize the acoustic cultural heritage. The sound carriers, called Helvetica because they are necessarily related to Switzerland, are divided into five sections, four musical - classical, jazz, rock & pop, folk - and one non-musical, which includes voices, audio books, radio plays, interviews, but also natural sounds and soundscapes.

«Our oldest items are wax cylinders with classical and operetta music from the collection of a private individual in Chiasso,» explains Günther Giovannoni, Director of the Phonotheque since 2019. «As far as music recordings are concerned, there is no obligation in Switzerland to submit a specimen copy to us. That's why we've been working for forty years, with the support of Suisa, other collecting societies and in collaboration with radio and other partners, to catch up on the collection backlog. For streamed content, Parliament has passed a law on the submission of mandatory digital receipts from 2027: a gigantic amount of material from which we have to choose. We are only obliged to conserve what is considered important, a challenging selection that involves people from different sectors.»

The sounding cultural heritage of a country

A cursory scroll through social media might make you wonder what is so important to preserve in all the often very commercial noise. «It's not for us to judge,» Giovannoni interrupts, «commercial or artistic value are not our only selection criteria. For example, we have a department that takes care of advertising. This could be considered less substantial or educational from certain points of view, but it is extremely important historically and sociologically, especially for specialists. The crucial question is one of sustainability: does it make sense to store so much material? What are the ecological and financial costs? Our guidelines allow us not to take everything so as not to be overburdened. For example, we also select new artistic productions: We let them rest for a while before we add them to our inventory.»

Photo: National Sound Archives

This requires a clear vision of what our country's sounding cultural heritage should be. «Our self-image is partly determined by remembered sounds,» explains Giovannoni. «Switzerland is small, but extremely diverse in terms of languages, cultures and special features. The archivist has the task of preserving this sound memory for future generations. We protect the past for the future.»

Of particular interest in this context is the speech and noise section, probably the richest in the Phonotheque. While it was the express intention to document a large number of bell ringings up and down the country, the soundscapes captured are sometimes a by-product of other recordings. They offer us sonic chronicles of certain spaces over decades: a rural market, an urban square. «The sounds change like our everyday lives,» says Giovannoni, «take the crunching of a glacier, which changes over time and will soon cease to exist. Or more prosaically: the municipality of Lugano has given us the recordings of municipal council meetings over the last 60 years. So you can follow the development of political discourse, linguistically, sociologically ... »

Among the musical documents, some take us through the history of the country, such as the estate of Hanny Christen: «Fifty tapes that were discovered by chance in the early 1990s. They preserve part of the »old and pure« traditional Swiss music and have revolutionized the way we look at it,» explains Andrea Sassen, Head of the Folk Music Department. "Or think of the K-Sound collection of Kiko Berta, who recorded some of the most important albums of the 90s, including gems that never made it to the market," adds Yari Copt, head of the Rock department.

«But it's also interesting to look at the present,» he continues. «Today, a generation of Swiss artists with a clear vision and high production quality is at work. And for everyone involved in musical heritage, this is a strong signal: the Phonotheque is not just an archive for the past, but a living place that documents the present and builds the sonic heritage of tomorrow. Preserving these productions today will make it possible in the future to say exactly what was going on in Swiss music at that moment.»

Looking to the future

So here we are preserving, but surprisingly also creating, as if to draw attention to what needs to be immortalized for the future: Bruno Spoerri is celebrating his 90th birthday on the Phonotheque's YouTube channel by delighting the audience with a wonderful livestream, masterfully recorded by Lara Persia at Studio Lemura. «This is the first in a series of concerts that we have been able to organize thanks to an extraordinary donation,» explains Giovannoni. «A kind of showcase: we are highlighting the value of our archives by offering a stage to those who have contributed to Switzerland's sound heritage. A tribute to these people who have given so much.»

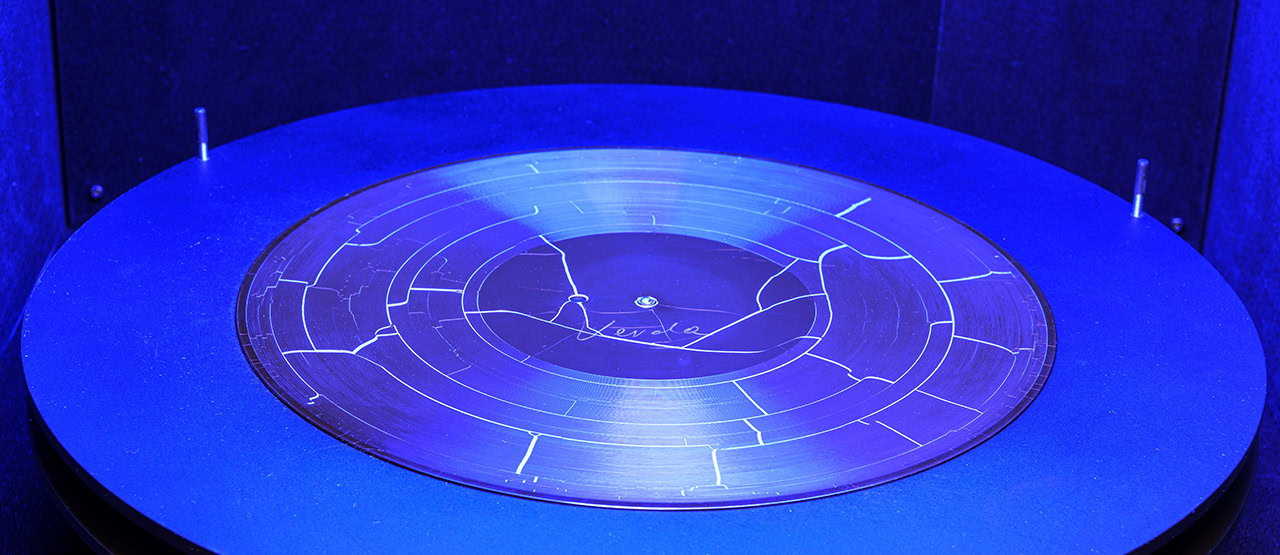

Here, too, the concept of legacy is expressed, the focus on the future. This brings us back to the technical challenges posed by storage media: a central theme for the preservation task of the Phonotheque. «We are closely tied to the technology. First and foremost with regard to the longevity of the carrier media. Shellac or vinyl records, for example, are robust. If they are stored professionally, we will still be able to hear their content in a hundred years' time. Tapes, on the other hand, slowly lose their information; 'home-burned' CDs have an average lifespan of five years. Playback devices also age and are subject to historical development.

One example is Sony's DAT cassettes, which were produced for 20 years. The company stopped production in 2007, but kept the licenses. At the moment, we still have a supply of tape heads, but when they are used up, we will face a serious problem. This determines our priorities in terms of digitization and preservation. It is a constant technical challenge to make the material tangible: We want to be a place where users are offered inspiration as well as opportunities to discover new things.»

This will is reflected in future-oriented technological projects such as research into the continued ability to read DAT sound carriers or lighthouse programs such as Visual Audio, a digitization process that makes it possible to save the sound content of a damaged record by photographing it in analog form and scanning the image.

An educational program with guided tours, workshops, lectures and school visits is aimed at a wide audience. It is also extremely important for the Phonotheque to raise awareness of listening and sound among the youngest members of the public. «Young people listen to music, but often in dramatically poor quality via their cell phones,» complains Giovannoni. «We need to teach them to listen consciously, also with regard to possible damage caused by overuse. They should become aware that sound quality is an important factor when listening to music and that timing, medium and format can influence perception. Many young people don't even know that there are other ways to listen to music than on their cell phones, and they have no idea of the differences in quality. You have to teach them, and you can do that by showing them the technical progress and the different sound qualities throughout the history of sound carriers.»