The demand for clarinet lessons at music schools is constantly falling, although hardly any other wind instrument offers a wider range of stylistic applications. From classical and folk music to klezmer and jazz - the clarinet is used everywhere. It is one of the most flexible and versatile wind instruments of all. The Swiss Wind Music Association has come up with all sorts of ideas to increase the focus on this instrument, which was highly valued not least by Mozart: concerts up and down the country, flash mobs, the largest clarinet ensemble, the longest clarinet note and a clarinet bus that was sent on an educational tour across Switzerland.

On the trail of the inventor

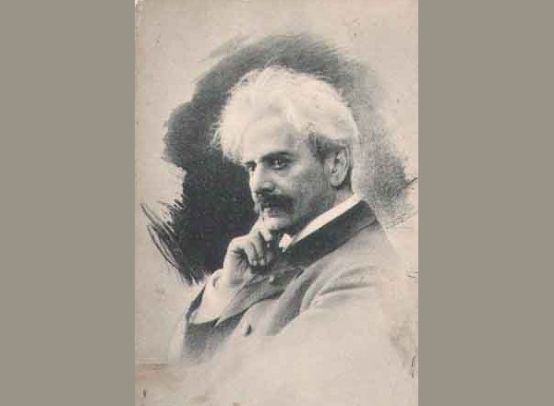

In January 2015, the Burgdorf Music School came up with an original and obvious idea to enrich the Year of the Clarinet. In the 1980s, the clarinettist and music teacher Andreas Ramseier came across the piano reduction of an opera at a flea market in Freiburg. It was the work of the largely unknown Nuremberg composer Friedrich Weigmann (1869-1939) entitled The clarinet maker on. The libretto was written by the musicologist, conductor and author of the Reclam opera guide Georg Richard Kruse (1856-1944).

The invention of the clarinet is attributed to Johann Christoph Denner (1655-1707), a famous Baroque musical instrument maker. Denner added an additional key to the chalumeau, which has the range of a major ninth, so that the instrument's range could be extended into the middle and high registers by overblowing. The sound of the upper notes was reminiscent of the clarino sound of the baroque trumpet, which is why the new instrument was given the name clarinet. Johann Christian Denner is also the main character in the opera. The extent to which the plot actually corresponds to the historical facts is beyond our knowledge today, but is of no further importance.

World premiere of the Burgdorf version

The clarinet maker was premiered at the Bamberg Theater in 1913 and was subsequently on the repertoire of several German theaters, including the Schillertheater in Hamburg. Today, the work cannot be found in any opera guide and apart from the one piano reduction, all the material is missing. It apparently disappeared during the First World War.

For the production at the Casino Theater Burgdorf, Roger Müller has written a colorful, multi-layered score for clarinet, violin, viola, cello, double bass, flute/saxophone, accordion, organ and guitar that lasts an hour and a half and is based on the piano accompaniment. Weigmann's music is difficult to categorize, but has late Romantic traits. In terms of content, it is a play opera, but the through-composed form contradicts this genre designation. A lot of text has been crammed into the solo parts, which is not exactly conducive to the melodic line and musical tension. Perhaps the work would have benefited from spoken dialog in the sense of a play opera. Duets are in short supply and vocal ensembles are completely absent. The few choral passages in the piece are economically taken over by the orchestra in the Burgdorf version.

An instrument is sung about

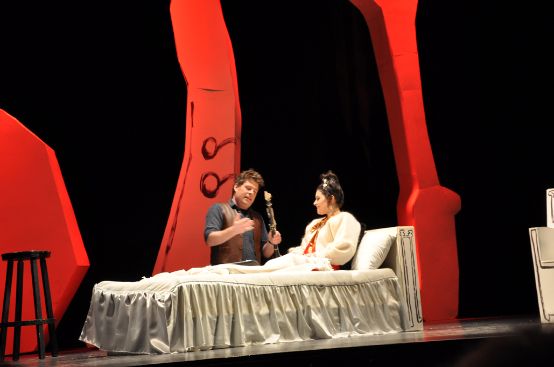

In Ueli Eggimann's lively direction and Matthias Egger's graphically conceived stage design, which was immersed in changing color constellations, a committed play with good vocal performances unfolded. Nine solo roles had to be cast, including the extensive title role of the clarinet maker Johann Christoph Denner, for whom Roger Bucher lent his agile baritone. His tinkering with his new instrument is accompanied by money problems and heartache. As soon as his clarinet sounds the way he wants it to, love also comes his way.

The composer and organist Johann Pachelbel appears as a customer of the instrument maker. Martin Weidmann succeeded here with a concise voice and a lot of comedy. Bettina Bucher embodied Denner's rich mistress Maria Clara Neufville, who is finally won over by Denner's seductive clarinet sound with the words "Let me be your clarinet". She was able to create the most beautiful, lyrically appealing passages of the piece with her light, well-conducted soprano. Barbara (Sandra Rohrbach) appealed with her tomboyish manner. In the trouser role of Gabriel Schutz, Diana Gouglina came up trumps with dramatic tones, while the shady Dr. Betulius (Fabio de Giacomi) was convincing in a buffonesque manner. The new generation, with Tobias Wurmehl in the role of the hunter Doppelmayr, Emanuel Gfeller as the clumsy assistant Zick and Sophie Aebersold as the girl, performed to great advantage. The Capella Burgdorf performed under the direction of Armin Bachmann.

Putting a world premiere of an opera on stage in just a few months is a remarkable achievement. The Burgdorf Region Music School can be proud of the result. The performance attended was the final performance on January 7.