I received so many responses to my survey on Facebook that I couldn't possibly quote them all in the printed article - especially not in the length in which I received them. Of course, I also had a guilty conscience: so much thought and effort must not go unnoticed! So here is a detailed selection of the contributions. A thousand thanks to everyone involved!

Editor's note: The articles are published in alphabetical order of first names. The original sound has been retained. With regard to spelling and punctuation, the editorial standards of the Schweizer Musikzeitung have mostly been applied. Unfortunately, some emojis from these texts cannot be displayed here as images.

Andi Gisler

I agree with my guitar idol James Burton: "Do you know music theory?"

"Yes but not enough so that it would hurt my playing."

The discussion about self-taught vs. studying or reading music vs. "playing by ear" is usually too short-sighted, outside of classical music it is usually or always "mixed forms" - I had classical guitar lessons for a few years, for example, but learned everything else "self-taught" or still do so every day. I can read music, but I've hardly ever needed it in practice.

But much more important is the inspiration and influence from all areas outside of music. In addition to life and personal experience, these include books, films, politics, etc. etc. In England, for example, the existence of art schools was absolutely crucial for the development of pop music. And pop/rock music cannot be considered separately from fashion, politics and society. As far as I know, nobody in Pink Floyd studied music, for example. But the band was formed in an "academic" environment - 2 or 3 members were architecture students. And this naturally had an enormous influence on the music, the presentation, the artwork, etc.

Perhaps jazz is in danger of becoming an ivory tower as a result of academization. But if you look at how many younger "jazzers" are working with electronic music or hip-hop, for example, I don't really see any danger.

I've just started watching the documentary about Keith Jarrett The Art of Improvisation on YouTube. And the first thing he talks about is exactly this: "The mistake is to think that music comes from music". And I think this is 100% true. As a musician, you can't avoid practicing intensively and relentlessly. But engaging with other genres can be extremely inspiring creatively.

Betty Groovelle

Yes, I am also self-taught. But above all it means that you develop your own language for music, you discover everything yourself. Things like dissonance, harmony, form. Fortunately, I have extraordinary analytical skills, an engineering mind. What has always surprised me is that time and time again studied musicians have been unable to answer my searching questions about why something is like this or that. I also don't understand why you have to practise improvisation, you listen to what notes fit and where the music wants to go, then you choose how extreme and how long detours you sing to them. So there are some things where I have a lot of freedom.

Because this wild music on an orchestral scale has always been in my head. In elementary school I always suffered with these horror songs with the same chords like Little Hansdiscovered jazz late in life ... finally something that corresponds more to the music in my head. I am jazz, but I never learned it. Now with the computer and DAW I'm learning step by step that my music can get out of my head and I can hear it.

Bruno Spoerri

I think I went through a fairly typical development up to the age of 30, like almost all my colleagues in Swiss jazz. There was no jazz training whatsoever and jazz was frowned upon - in some conservatories it was forbidden to play jazz. There were a few people who dared to do the balancing act, for example the pianist Robert Suter, pianist of the Darktown Strutters and piano and theory teacher at the Konsi Basel.

I learned the piano as a child, first with the pianist of my mother's trio (she was a violinist and had a trio with whom she played in the café - and occasionally performed as a soloist in the symphony orchestra), then with the top guru of Basel piano teachers, who completely put me off playing the piano. At least I learned to read music to some extent. Then friends started playing jazz and I wanted to join in. The only vacant position in the band was that of guitarist, and I asked a guitar teacher what was the quickest way to learn. He recommended the Hawaiian guitar, and I did that for a while until I realized that it was probably the wrong instrument.

The teacher still had an old saxophone and he sold it to me. I then went to a boarding school in Davos for two years, and there the saxophonist of a dance orchestra, Pitt Linder, gave me my first real sax lessons, and he let me play a few swing pieces until I understood how to phrase in swing style. We also had a trio at school with whom I practiced a lot. Back in Basel (1949), I listened to AFN on the radio every night, Charlie Parker, George Shearing etc.

My first gigs were in dance classes, jams at the Atlantis with the pianists there (Elsie Bianchi, Gruntz, Joe Turner), then the first jazz festivals. The pianist Don Gais lent me his book and I copied out about 100 pieces by hand. In Basel there were old style bands (Darktown Strutters, Peter Fürst) and the modernists around George Gruntz. I played everywhere, graduated in 1954 and began to study psychology. Then came my first prizes at festivals, my own bands (big band), then the Metronome Quintet in Zurich while continuing my studies. And I started arranging, composing etc. - the clear idea was to work as a psychologist and make as much music as possible on the side. Then I had two years of lessons with Robert Suter, and he taught me harmony and counterpoint.

Then I got married in 1960, continued to live the double life and started playing in Africana. Then, by chance, I got a small film music job for Expo 64, which brought me into contact with an advertising agency, I had a few more jobs - and at the end of 64 I was suddenly asked if I wanted to join a new commercial film company as an in-house composer and sound engineer. I took the leap, even though I had no previous training, and then learned how to do it in practice. And then I came into contact with electronic music and with so-called beat musicians (The Savages), it was all learning by doing - with every new job I had to learn something - then also technically - partly because I had problems with the recording studios at the time, I opened my own studio until I fell flat on my face with my own productions (Hardy Hepp, Steff Signer, etc.) etc. etc. etc.

I mean, all my colleagues had similar prerequisites: Lessons from piano teachers, or even in a brass band - classically oriented, then learning on their own, especially together with friends, playing a lot and trying everything out. Gruntz was practically the only one who went from being a car salesman to a professional - Ambrosetti and Kennel ran companies. Many were also students - but many of them gave up playing after graduation. I did a survey in 1958 (that was my thesis as a psychologist).

One more thought on the history of jazz: early on, there was the myth of the self-taught genius - the original Dixieland band advertised this even though all the musicians there had effectively had music lessons - they presented themselves as natural geniuses, which was good advertising. Blues musicians, however, were often untrained - but they also learned mainly through contact with older musicians. And in rock it also became a trademark that they had learned everything themselves - which is usually not exactly true. In any case, there are a lot of idealized CVs on the subject ...

Bujar Berisha

It's similar to being a foreigner. You live the same life, eat the same food and do roughly the same things, only the language is different. That excludes or arouses curiosity. And like everything, everything has advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that you have your own handwriting right from the start, which others have to/want to develop later. On the other hand, autodidacts don't even recognize their own handwriting at the beginning, but see it as a shortcoming ... For example, some immediately hear that the violin is poorly bowed, even though they can't locate a note in a scale. Trained violinists may need years to hear how the bow makes the strings vibrate.

Christoph Gallio (DAY & TAXI)

I bought myself a saxophone at the age of 19 and spent 2 years self-taught (free improv and free jazz in bands) ... then learned to read music in 2 years (Basel music school with Ivan Rot) and then a year at Konsi Basel (also with Iwan Roth). And when I was 29 years old, 2 afternoons of 'lessons' with Steve Lacy in Paris. That was it for instrumental lessons. As a composer, I am totally self-taught.

In Basel, I was in a shared flat with Philippe Racine (flute - now a professor at the ZHdK, mostly composes as he can no longer play due to dystonia). He was at the Konsi before me. Super talented and, in a duo with Ernesto Molinari, was passed around and celebrated as an interpreter of new music. That's all well and good. But as a free jazz musician you were ridiculed and not taken seriously - that was an unspoken basic mood. A fellow student (also a saxophonist!) at the Konsi called me a soul salesman back then.

I was involved in the freescene (in Basel and Zurich) ... then very quickly sympathized with the jazz scene (which in turn was not appreciated in the freescene - you quickly became a traitor back then. It was all complicated!) The free scene also wanted to be part of the new music scene and wanted to be taken just as seriously as the graduated new musicians. There was still E and U music. And for a long time "we" were declassified as U-musicians (there were few inside - except for Irene). Why? Because we didn't go through the consi mills. In short: if you were at the Konsi, you could play. You knew how music worked.

We free jazzers etc. (we saw ourselves as e-people and were all self-taught - you can't study at a university) ... of course we also went to the same venues and funding pots. These had to be defended. There was the MKS (Musikerkooperative - today Sonart) and they were keen to gain acceptance for free improvisers. So that we could get our hands on the pots (which were never full either!). But these pots were fiercely defended and it took decades for that to change a little. And when money is involved, it quickly becomes about power. Who gets it, who distributes it. Who is a friend, who is not.

DAY & TAXI: Drummer Gerry Hemingway (67) is totally self-taught, as am I (65) for the most part, and bassist Silvan Jeger (37) of course has a master's degree in bass playing. There are actually no more self-taught musicians today. You can't teach at a music school these days without a diploma. Silvan once had his own band, which I thought was great ... it wasn't fully developed yet, but it was on its way. Unfortunately, he couldn't sell it very well and the members were passive (very normal - didn't help with finding gigs etc.), which disappointed him and after a year he gave up the band. Unfortunately, zero stamina. Or the motivation was too low ... it was too slow for him ... I don't know...

Anecdote: We had our last gig in Baden recorded. The technician is a master jazz drummer and about 25 years young. After the gig - which he liked - he asked me about my training. You know the answer. And I told him that Gerry (famous and former lecturer at the Lucerne Jazz Academy) was actually totally self-taught. Then he said: OK, I get it now. There's something that I'm hearing for the first time or that unsettles me. It irritates me. And he spoke of an energy. I think he sensed the commitment, the inner fire or something - well, that sounds very esoteric now ...;-) ... In any case, I was delighted by this episode. To realize that a young musician was aware of something that unsettled him and motivated him to think. I think he was thinking about music, what it can do, what it should do - or quite simply about how ...

Daniel Gfeller

Music is the disease that you try to cure with music. "Was he an animal, since music seized him so?" (F. Kafka/The transformation). One is condemned to lifelong "self-realization" - with or without formal education. Even deconstruction qua punk rock has failed ... hopeless. We pride ourselves on finding our own soul sound until a teacher, or love (un)fortune or life trims the tender shoots ... Music is also "marking territory" - where I sound, I am. Formal training takes away the burden of having to be the absolute authority all the time (I think).

Daniel Schnyder

Everyone has to learn for themselves, no one can learn anything for anyone else, so by definition every creative mind is a lifelong autodidact.

Dieter Ammann and Bo Wiget (Dialog)

DA: One of the advantages of being self-taught is that you can judge music according to the motto: I like this ... I don't like that. However, this is also a disadvantage at the same time, because you are denied the ability to make in-depth judgments.

BW: As I understand it, being self-taught doesn't actually mean that you don't know anything.

DA: As someone who was completely self-taught in parts (trumpet, electric bass), I would never say something like that.

Emanuela Hutter, Hillbilly Moon Explosion

I have been learning to play the piano since elementary school. I took classical singing lessons in Zurich and New York. I learned to play the guitar on my own.

I have had various different experiences with this. When I was still singing classically, I always had to switch up my singing. Oliver from the Hillbillies almost went up the wall when my voice got too stuck in classical music because of performances with the classical ensemble. The focus there is always on resonance. And they work intensively on the sound of the vowels. Groove and intelligibility sometimes take a back seat. The advantage: I can perform with the Hillbillies every evening for three weeks in a row without getting hoarse and still sing out into a room without a mic and generate a lot of resonance, which always amazes the audience.

At some point I heard and observed that my favorite female singers from blues and jazz use consonants to shape their sound. I do the same now, which is part of what makes the Hillbillies such an extraordinary mix: my classically trained voice and the sound of the instruments.

As far as the piano is concerned, I always notice that my way of writing songs on the piano is still influenced and limited by the pieces by Chopin, Grieg and Bartok that I had in my head a long time ago. Hence the old-fashioned movie music ambience of those songs. See or listen here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nF75w7yTY8c

I taught myself how to play the guitar. To write songs. And occasionally I had guitarists show me techniques, such as finger-picking. However, I never took regular lessons. I'm limited and play a rustic rhythm guitar, although I'm pleased that my woody style is now also appreciated and used in the studio. Sometimes even preferred, even though I work with guitar cracks like Joel Patterson or Duncan James.

Both the serious learning of an instrument and self-taught learning have advantages and disadvantages.

Ernst Eggenberger

I am a songwriter you can find me on Youtube. I played concerts and made records with a jazz rock band Andromeda in the 80s. For the last 7 years I've been lucky enough to record concerts and CDs with Felix Rüedi on bass. He went to jazz school and is an accomplished fret and fretless bass player. For the CD recordings, he wrote out the charts for the studio musicians using my template. He always said it was lucky that I wasn't trained, because otherwise I wouldn't be able to write such free songs, I don't know any rules, so I don't have to stick to them. He always said that there was always a trap somewhere in my songs where he had to be careful.

I once had a TV appearance with the Oberalp band, they have two clarinettists, one did the consi, the other can't read music, and they've been playing together for over 30 years. There are always pros and cons to everything.

Ernst Hofacker

As an old forest and meadow rock'n'roll guitarist, I say: as a self-taught musician, I have always kept the necessary impartiality towards the music and the instrument. But a few lessons, copying here and there and the will to play the fourth chord never hurt! (Editor's note: three guitar emojis and 🙂 )

Hotcha Means Hotcha

In the 60s we were all self-taught, we copied where we could, legends tell of guitarists who deliberately played with their backs to the audience so that you couldn't see what they were doing, sometimes we were also taught something by guitarist friends, I have The Last Time from Jessi Brustolin's father, including Gloria and the barré chords ... which also explains why beat then became krautrock and later progrock, the former unmistakably astonished again and again by the ingenious pentatonic that could be noodled up and down, the latter unmistakably with an eccentric ambition on the way to eye level with the classics.

Back in 1967 our bass player from a good family said to me, "Bach is only for intelligent people", it was clear what he was trying to say ... but that was the seed. After that, in order to be able to play sax, I had to know and understand harmonies, so I'm happy today when I see YouTube videos for soundbytes sliders with a fetish for vintage electronics, where they are explained II-V-I

Jessi Brustolin

My father gave me House of the Rising Sun After that, the book by Peter Bursch was the order of the day; instead of notes, numbers explained fingerings. Then actually a few years of jazz lessons, whereby the poor teacher despaired of me, I always wanted to play punk and metal songs instead of Robben Ford. That's still the case today :-))

John C Wheeler (Hayseed Dixie)

Guitar yes. Piano no. I was classically trained, but that comes with advantages and disadvantages - mainly that means good for the technique, bad for the groove.

John C Wheeler and Stephen Yerkey (dialog)

SY: I'm self-educated... I want to write a memoir on what it's like to play music for fifty-five years with your head up your ass.

JCW: In 3 years, I'll be able to help you write it.

Jonathan Winkler

I had a few lessons but in the end I learned most of it by listening and playing - I'm limited accordingly ... I sometimes regret never having learned how to play the guitar properly.

Käthi Gohl Moser

Even after almost 50 years of teaching and establishing the music education master's degree programs in BS: There is no learning that does not happen exclusively in/by the learners themselves. Among other things, we are gardeners, so we can provide better (and unfortunately also worse) conditions, we are mirrors for promoting self-awareness, but above all we can infect and set music/fire, but it is the students themselves who burn ... Conclusion: training is never the only prerequisite for fantastic music. (Star emoji)

Kno Pilot

I'm largely self-taught and I think that's an advantage with indie songwriting stuff (which is what I do). Last week we were playing a new song (me bass and vocals) and I heard an "interesting" note in my head that I wanted to incorporate into the bass line. When I found it on the fretboard I realized it was the octave of the root :-)) . Trained musicians would never call it an interesting note and might not even play it because it's too simple

Lukas Schweizer

I had many years of classical guitar lessons, strictly according to sheet music. When I started playing my own music, I first had to learn to free myself from the "rigid" notes. And I only really understood the guitar system when I started playing more freely. Before that, I was far too attached to sheet music. I also sang in choirs (mainly classical choral music) for a long time. For my own music, I had to rediscover my voice, find out what was possible with it and what I liked. This also involved a freer approach to the voice as an instrument. However, the well-founded basic musical training that I enjoyed is also important to me and forms the basis for many things. For example, I'm currently teaching myself to play the piano and my knowledge of music theory is already helping.

Marc Unternährer

I studied classical music, improvised and played jazz (in the broadest sense) during my studies and it took me years after my training to free myself from certain things and to let go of ideas about how I should and may sound. In jazz, I learned more and more by often being overwhelmed, I am self-taught. I wouldn't want to miss my studies, but today I no longer play strictly classical music.

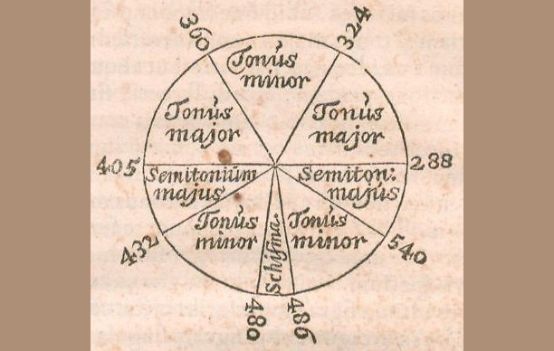

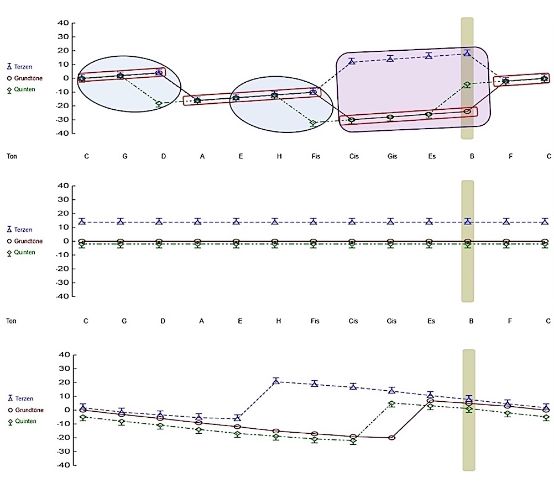

Martin Söhnlein and Dieter Ammann (Dialog)

MS: With professionals you have twelve tones - with amateurs all of them.

DA: That's not quite right - microtonality contains many more tones ...;))

MS: You're right, of course.

DA: And then in contemporary music (which has been called "new music" in terms of genre for over a hundred years, since the collapse of "tonality") there is also the whole range of noise ... Artistic expression per se knows almost no boundaries.

MS: Totally agree. The journey - although the destination - doesn't even play such a big role.

Matthias Penzel

My experience is no different to walking on your hands: If you teach yourself something, it takes longer, e.g. training your ear - and it seems to me that it's always much more deeply engrained in your marrow and bones. Because then you play something as ludicrous as a 4/4 time signature, for example, as if you had just invented it. That's difficult to teach and also difficult to convey to others. If you watch AC/DC (not my taste, but an objective observation) in the concert hall and see how people are tapping along right up to the very last row, then you can assume that nobody knows why, but if you talk to drummers about it, you will immediately come across a lot of drummers who can explain it in detail. The how is not so easy to teach ... or conventionally unusual; perhaps there are more 'spiritual' didactics. But hardly at the conservatory, I suppose.

THEN the qualities of a musician in pop are by no means just the craft. The Edge can't or couldn't play chords, Eddie van Halen couldn't sing melodies, Ozzy could never sing, ditto Anthony Kiedis and actually most hard rock singers, so they had to ... like Pete Towshend with his ugly big nose: compensate. And that's basically the story of rock.

Compensate with compositions that work differently, or with crazy playing (something completely different, thousands of readers of tablatures get into it every month ... they even create things, e.g. Van Halen's Beat-It-Solo, he never played it like that himself, but Quincey Jones glued it together from several recordings ...). So, these are very different qualities that ultimately make musicians/bands into something that stays in people's heads for a long time.

In this context, I think you should actually talk to the musicians from Celtic Frost. In terms of long-term effects, it's pretty fuckin phenomenal.

Matthias Wilde

I am self-taught, and this is somehow liberating, but can also be an obstacle. Good theoretical knowledge certainly makes it easier to learn other instruments and new styles. As a self-taught musician, there is a danger of going round in circles. Of course, this is also possible with well-trained musicians and also depends on the person, but with theoretical knowledge you can think your way into new situations more quickly, I think. Oh, what do I know! Everything has its justification as long as there is fulfillment!

Micha Jung

My playing styles are linked to the people I learned them from: various flamenco styles from maestro Ricardo Salinas, American folk picking from Martin Diem (Schmetterbänd), various fingerpickings (Leonard Cohen), E-Git (Schöre Müller), Rhythm. Guitar (Tucker Zimmermann, Joel Zoss) etc.

Michael Bucher

I learned guitar self-taught before I went to university, I did go to a teacher here and there, but never regularly and I probably had 5 lessons before I went to university. I was probably an anti-school child and still have trouble understanding today that what you want to be able to do should be taught in a school. I am also a multi-instrumentalist, I often mix my own recordings, I also make the recordings, my environment is large and willing to give tips when I have questions, the internet is full of knowledge, that's how I learned most of my skills. Of course, there's no diploma for that, right 😉

Nevertheless, I still teach at the ZHDK from time to time, and I always have students who want to come to my lessons. I think that's great, the interaction with the "kids". The universe is full of apples, you just have to pick them.

Nick Werren

I am also completely self-taught. This can occasionally trigger complexes when working or being together with jazz-trained friends or fellow musicians, which is why I don't like to call myself a musician in the scene, even though I've spent half my life making music.

Over the last few years, I've tried to catch up as much as possible with my children's music lessons and homework. I now know which line the C is on, but somehow that hasn't helped me much.

Nikko Weidemann (e.g. Moka Efti Orchestra in the series "Babylon Berlin")

I learned the most from my students when I was a lecturer for 10 years. Without ever having studied. Before that, for 4 decades I always went with a divining rod to wherever I suspected a creative vein of gold. I believe that having to reinvent yourself is the most important source. Putting yourself in a position that you can't easily get out of demands the best from you.

The problem and the infirmity of jazz is its schooling, its academization. Giant steps as a one-way street from which there is no escape. Of course there is traditional knowledge, Keith Richards also has a lot of it, but he evades analysis. In his great book, he says exactly how his open tunings are, he uncovers the "code" and makes it public. Anyone can have it and yet no one has Keef or, for that matter, himself, until he or she is prepared to pay the price.

Richard Koechli

This probably also has to do with the type of learner (I tend to be more self-taught). To describe theory, for example, as fundamentally "hurting" for authentic music doesn't do justice to the whole thing. I've managed to get just as much theory as I needed (quite urgently) for my work - feeling, passion, a fine ear etc. were not enough for me to be able to realize my potential. Theory is a relatively small, but very valuable part for me to be able to orient myself in music, to be able to reproduce and communicate things, to ground myself. Of course, it has to be able to step back at the right moment, especially on stage. I'm schizophrenic enough and, especially with slide guitar, I can sneak from note to note without a clue, just with my ear, curiosity and heart - but I can work all the more refined (and reduced), especially when arranging and developing, if I know exactly what theoretical function each note has.

I think the problem is that people seem to want to play opposing things off against each other - the self-taught and the academic, for example. In reality, there are millions of mixed forms. No one in the world is exclusively self-taught or academic. Everyone acquires the necessary tools to be able to work in their own way. And everyone can learn from everyone anyway, for the rest of their lives ...;-)

On an emotional level, I can definitely say that at the beginning of my career as a professional musician, I was very afraid of not being able to hold my own and be sufficient - and that there were moments when I wished with the greatest longing for some kind of training or diploma that could have conjured this fear away, a label "now you can be a professional musician or even an 'artist'", so to speak. At the same time, I knew that my place was elsewhere, that I would have been overwhelmed at a professional jazz school, for example - and so, for better or worse, I had to learn to overcome this fear on my own. I succeeded, but again, to be honest, not through my own efforts - but that ... is another topic in a moment 🙂

Roland Zoss

For creative spontaneous musicians, sheet music is a hindrance. I hardly know any musicians from the rock-folk-songwriter-flamenco genre who write down sheet music. Personally, after vocal training, I had to learn to use my voice intuitively and atmospherically again. Instead of just paying attention to the sound. But what I have retained is the ability to sing PURELY and without pressure on the voice. Along the way, I developed an absolute ear for music ... thanks to heigisch - Universum ...

Saadet Türköz

I am certainly one of the self-taught musicians as an improviser and vocal artist. Today I see this path - in which I read without sheet music, without musical (education) - as a joy. I see the advantage in this, because you listen inwards, which gives you your own artistic expressiveness and color. The only disadvantage I find is when I get requests that have to do with written compositions. I then find it a shame that I have to turn it down, especially if I think it's an interesting project.

Simon Hari alias King Pepe

- In the meantime, I am a happy autodidact.

- However, I only found this out after working with many professionals. They told me about their laborious de-learning processes.

- But it took far too long for me to get to know these professionals (and by that I mean trained musicians). And that in turn has to do with the fact that I'm self-taught. I always thought: "Oh dear, I'm a dilettante, I can't ask really good musicians to work with me. I can't do anything!

- I am very glad that I plucked up the courage and did just that. And that's when I realized what a nice addition: it's not just that they can do some things that I can't (of course). It's also the other way around: I can do some things that they can't and appreciate. (performing * thinking not only musically, but also conceptually: wanting to tell the whole story * arranging unconventionally ... to name a few)

- Of course, learning on the go didn't hurt. What I like about it is that I have acquired music theory super-selectively. I still don't know much about a lot of it, but in some areas I've naively got stuck into it and developed my own language.

- Any trained musician could certainly do that too, but perhaps the hurdle is higher when it's "school material". I then picked up a music theory book and for me it was like a magic book oooh, now I'm delving into the most secret secrets of music, what a stunning feeling.

Tom Best

I am a self-taught drummer. Because of this, and because I've been playing the instrument for a long time but never consistently, I find it difficult to compare myself within the drumming scene. I also lack a certain systematic approach to my learning history. Instead, I just learn and practise what fascinates me. And in this respect, I don't have to fulfill the requirements of any genre - at most, of course, the rock'n'roll band I play in. So on the one hand, I'm inhibited from comparing myself with the "pros". On the other hand, I enjoy a certain fool's freedom in my permanent amateur status ...

Tot Taylor

I am totally self-educated - gtr, bass, piano, harpsichord, etc, synth, drums, cello, trumpet, French horn. Don't read music. The 'Ups' outweigh the 'Downs'. But there are 'downs'. Prejudice mainly. It has simply meant I can make a varied album or recording all by myself whenever/wherever I like. But I love playing with other people, so usually make a BIG decision about each album before I begin. The current FRISBEE was mainly with Shawn Lee, Drums, Paul Cuddeford, guitar, Robbie Nelson and Joe Dworniak on engineering and mixing. Recorded at RAK London and at Riverfish Studios, Cornwall. In pre-production now for the new one, that will be exactly the same set-up.

Urs C. Eigenmann

I don't have a single diploma. I've been playing and composing music for what feels like 100 years, was a piano teacher - Gabriela Krapf, for example, graduated with Best Musik-Matura from the Kanti Trogen - and was a music and theater teacher and school band leader at the Flawil upper school. I have recorded many all-round albums and still live happily and actively as a musician and, more recently, as an organizer again.

Ursus Lorenzo Bachthaler

The pragmatic answer to this is that few jazz musicians have the enormous talent required to be self-taught in today's increasingly academicized jazz world. I think that today 99 out of 100 professional jazz musicians have a diploma, also with the ulterior motive that you need such a certificate in Switzerland if you want to teach at a music school/grammar school/university later on. And only very few make a living from the concerts. The music that emerges from this academization is definitely different from the music that almost all my professional jazz musician friends always fall back on when they run out of inspiration 😉 We live in different times that produce different spirits & different music. What I personally find very unfortunate, however, is the gradual disappearance of venues that provide social hubs in the form of late-night jam sessions and would offer talented musicians the chance to acquire or improve their musical skills even without an academic education.