Memory research

Melanie Unseld gives an introduction to musicological memory research in "Music and Memory".

"Memory is something we performers don't like to talk about - mainly because we're afraid of losing it." This is what the Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt once said. The fact that professionals can play by heart for hours on end, usually without making mistakes, is basically a miracle. In fact, our brain memory is as fascinating as it is almost impossible to penetrate. Beyond the extremely complex and as yet barely researched interplay of hundreds of trillions of synapses, this also applies to the topic of "music and memory". Although it is immediately obvious, it is still difficult to grasp.

Music and memory by Melanie Unseld is a study book. The professor, who teaches in Vienna, aims to provide an overview of musicological perspectives on a subject that has been significantly promoted by cultural studies, for example by Jan Assmann's book The cultural memory. Identities therefore play a role, for example, where the subconsciously anchored Marseillaise or other hymns create national awareness. Other areas of research include aspects of canon formation and reception research. Why are some things remembered and why not? Why have these or those composers and far fewer female composers prevailed? Unseld naturally also touches on monument preservation and politics with such questions. She mentions, for example, the temporary ban on the Marseillaisewhich, due to its revolutionary potential, was to disappear from memory for a time, just like some works by Russian composers that were banned under Joseph Stalin.

It is not always easy to follow Unseld. She changes perspectives in minute detail. From the absolutely important role of music in the lifelong formative teenage years, she jumps to music didactics, dementia research or a falsifying memory that is commonplace in biographies. As if that were not enough, memories also play a role in the aesthetics of composition. Composers recall predecessors by quoting them. And: sonata form, variation movements, verses and choruses make it clear that music almost always plays on the keyboard of memory. Unseld sums up this particular narrow approach by writing about the experience of time: "Music can deal with time in three ways. It can construct time (through rhythms or the course of form, through composition), imagine time (for example with historical performance practice or music historiography) and make time perceptible (for example through the correlation to the heartbeat or when time passes while practicing or attending a concert)."

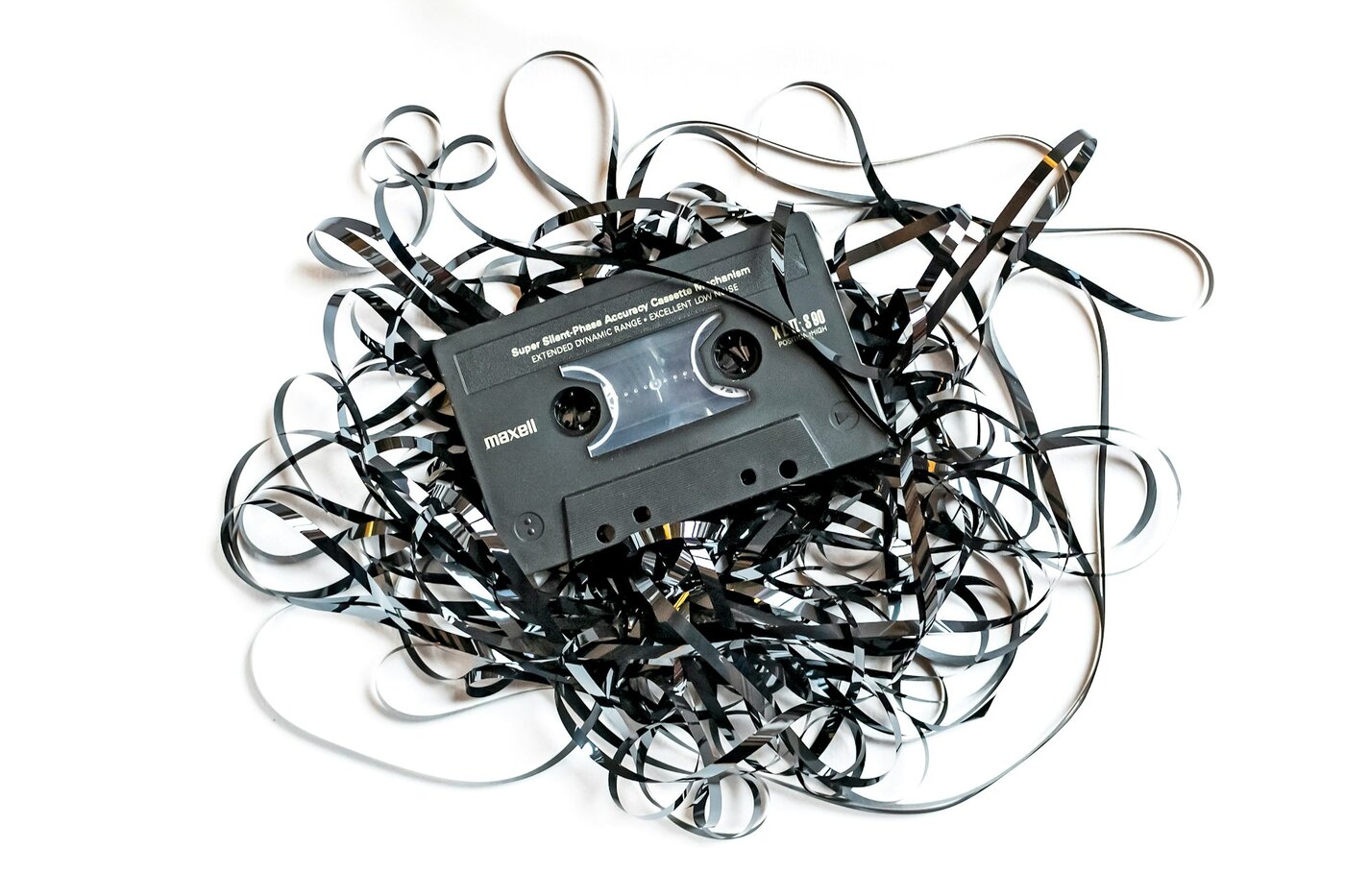

For the time being, it is impossible to foresee where this complex field of research will lead. It is nice that Unseld's excellently edited book moves away from cool formalism towards a more human approach to music. In the end, however, it cannot be overlooked that memory is (so far) difficult to grasp and is often very different from person to person. In this respect, music in turn has to do with memory, because both areas seem like a pudding that cannot be nailed to the wall.

Melanie Unseld: Music and Memory - A Study Book, 298 p., € 29.90, Rombach Wissenschaft, Baden-Baden 2025, ISBN 978-3-96821-886-1