Shouting with a united voice

Maybe it's just a chain of circumstances, maybe the measure is full, but in any case, musicians from French-speaking Switzerland have spoken out to express their concerns and the increasing difficulties in practicing their profession.

At the beginning of May, the cellist Sara Oswald published an open letter on social media in which many artists recognized their own situation. She speaks of an "... exhaustion from always having a meagre salary while the cost of living is rising. An exhaustion of always having to apply for a premium reduction from the health insurance company, because without it I can really pack it in. Exhaustion from having to create tons of dossiers to realize my projects."

She reminds us that professional training does not protect musicians from precarious circumstances: "I studied at the HEMU Lausanne and completed a master's degree in baroque cello at the HEM in Geneva. I've been a professional musician for 23 years. There are months when I earn 400 francs because I can only play one concert in 30 days. Yes, I could teach, I could play in an orchestra. But that doesn't suit me at all. I like writing music, composing for projects, giving concerts. That's why I learned this profession. It takes time to create music, practise my instrument, promote concerts, do administrative work (more than half of my time). Who has the energy after a day of lessons to sit down in their practice room and find the inspiration for an original composition? Because, in addition to being a musician, you also have to learn to sell yourself. I can say that my work takes up more than 100 percent of my time. To be clear: I only do that: work. And for free."

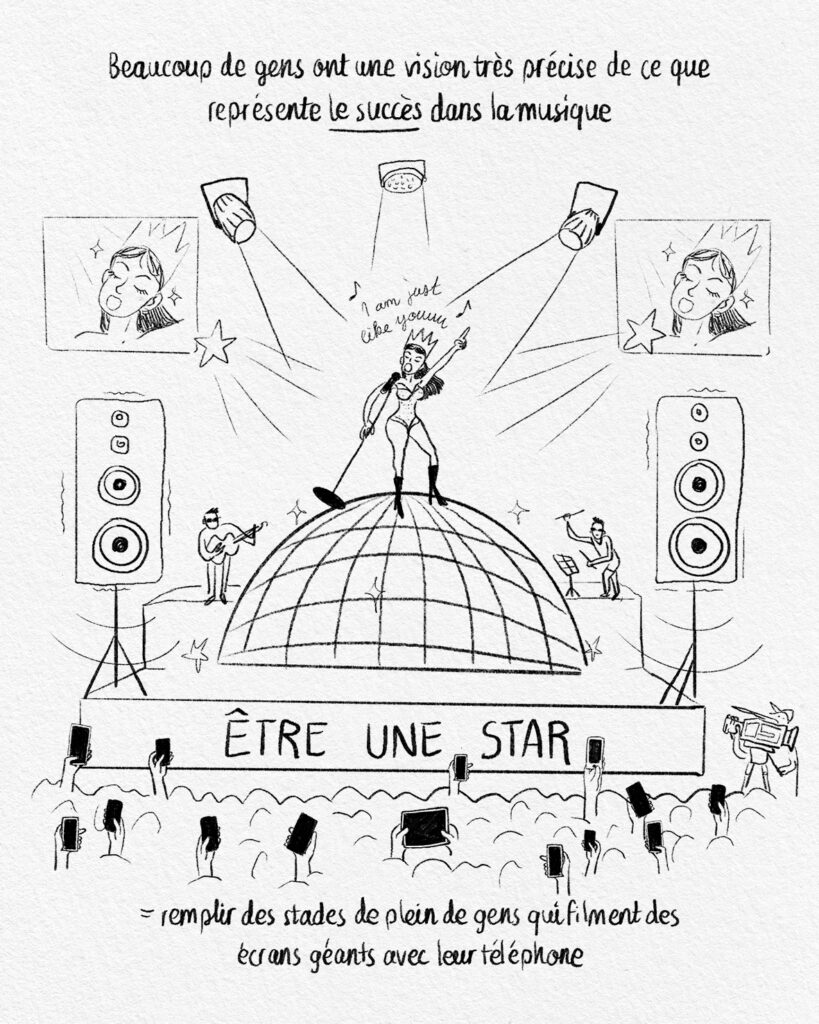

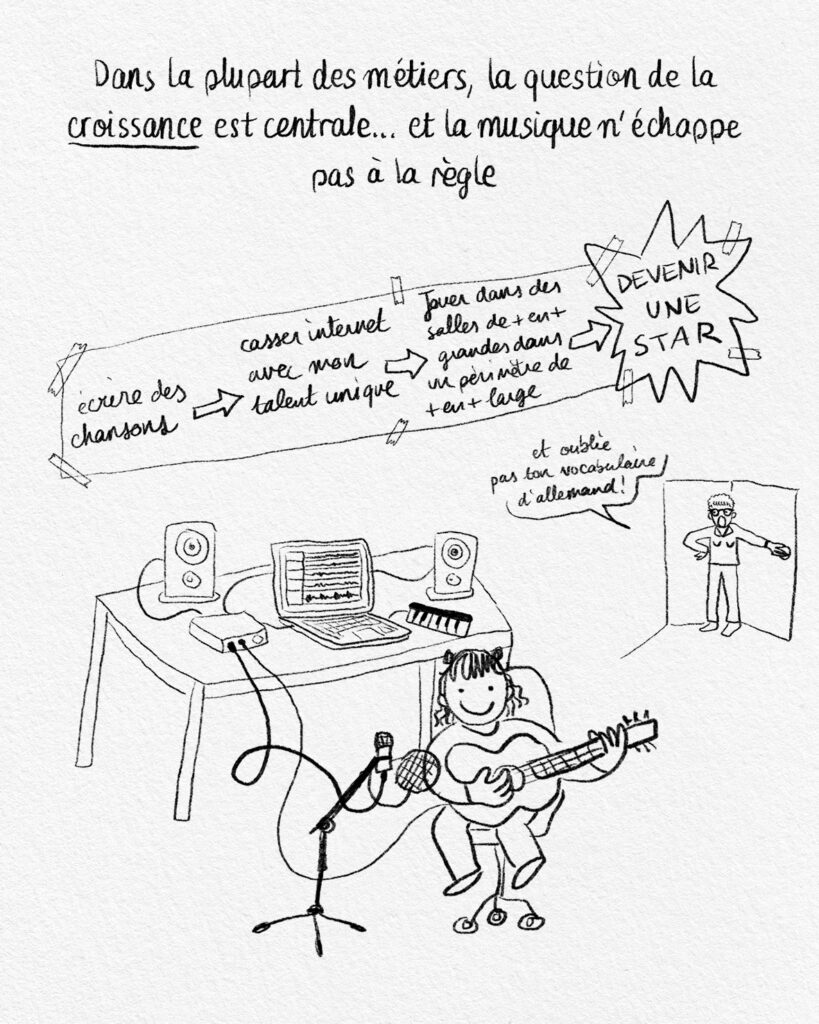

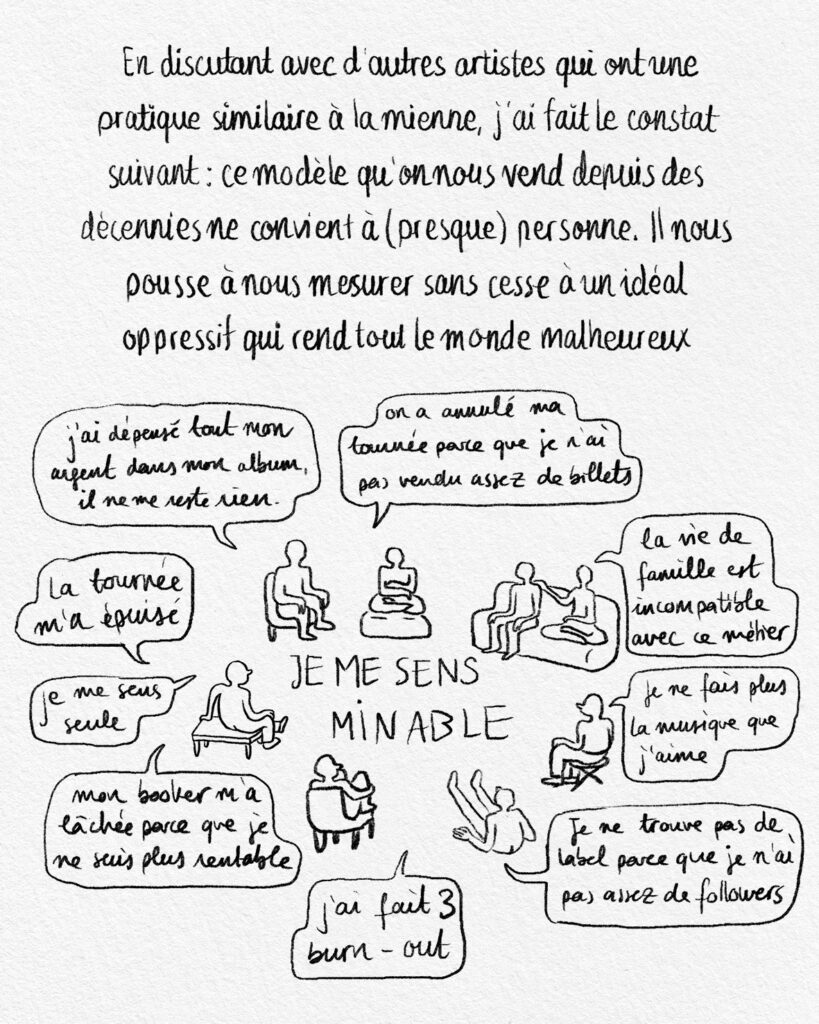

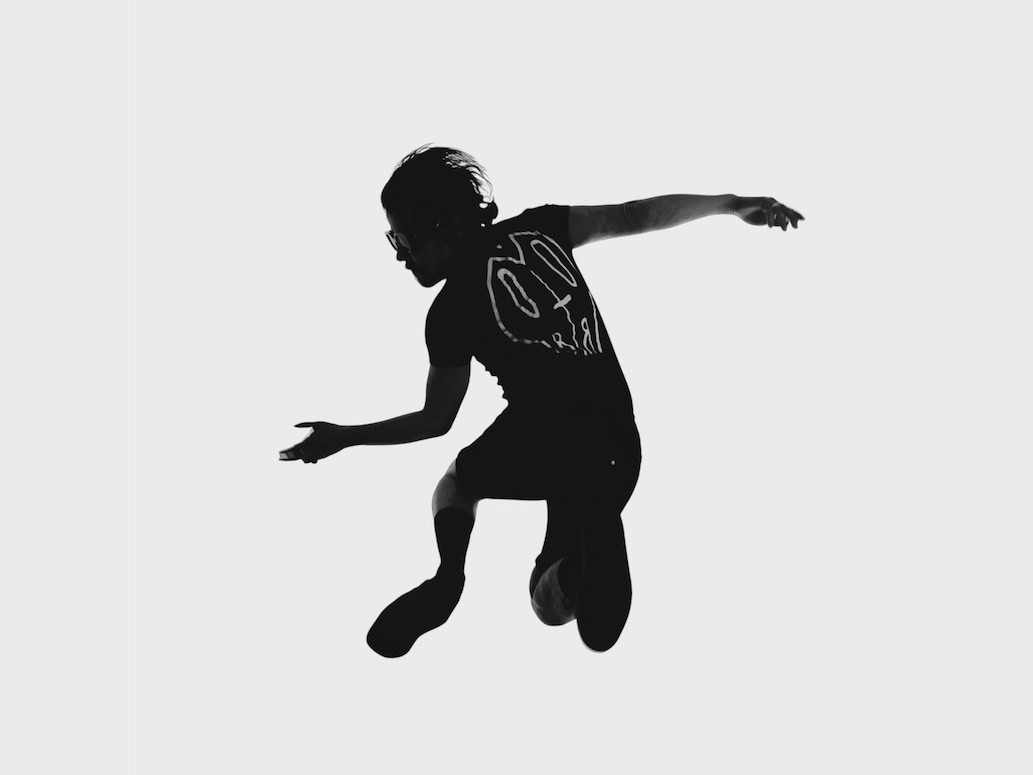

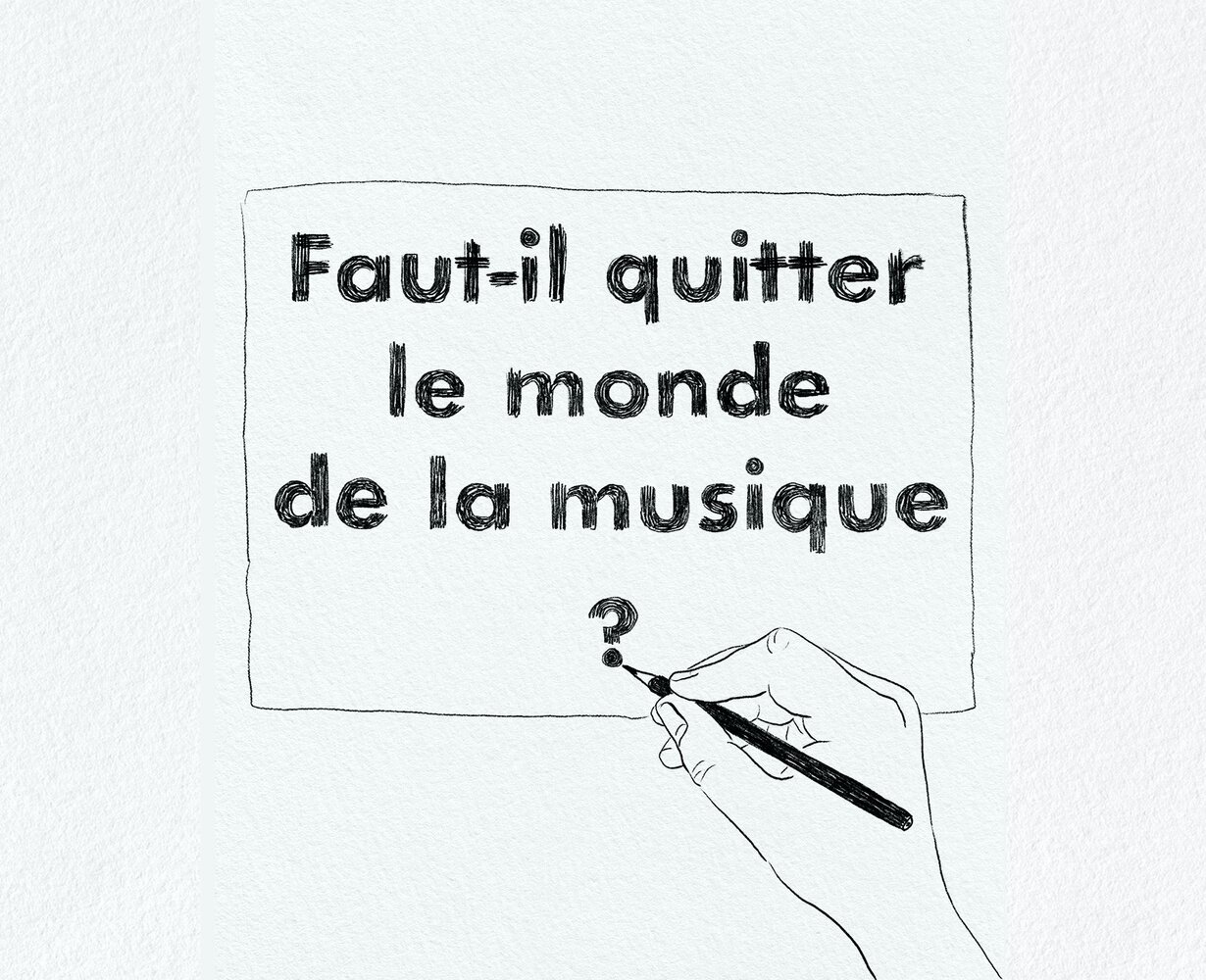

The singer from Valais Meimuna has expressed her dissatisfaction in drawings: a series of 14 illustrations that can also be seen on social media. They reflect the same concern and address an existential question: "Do I have to give up music?"

Paléo deep beater

On 2 May, a third artist, singer Moictani, who will be performing at this year's Paléo Festival, will take up the subject on the RTS radio program. We hear that she too has to make do with fees of 200 to 300 francs per concert and that Switzerland's biggest festival is in no way more generous. The entire budget flows into the dizzying fees of the stars. People dream of a Paléo that would invite two fewer celebrities and pay the lesser-known artists correctly. It would then perhaps sell its 200,000 tickets in 30 minutes instead of just 13.

Overall, we dream of a society that is aware of the indispensable role of culture and the need to represent our own culture instead of delegating cultural life to individual stars from across the Atlantic. This requires support from the state that is not questioned every time money is needed to save a bank or compensate for customs duties.

The Fee recommendationswhich were recently drawn up by Sonart, are a very good step in this direction. As her open letter has triggered numerous reactions, Sara Oswald is now conducting an online survey that will ultimately result in a manifesto. It will most likely be published in the French-speaking Swiss daily newspaper Le Temps appear. In order to achieve an improvement, musicians in Switzerland agree that they must act together and open their mouths - or rather: shout - with a united voice. The Swiss Music Newspaper is precisely for this purpose.

Open letter from Sara Oswald: Invisible

"It started a few years ago. A touch of tiredness. An emerging irritation at still having to explain that I would like to be paid when I play on this or that album or when I give a concert. A growing dismay at the unrealistic ideas people have about the life of an artist. I still hear the same thing: it's nice to be able to live out your passion.

The years go by and all this is compounded by exhaustion, combined with the thousands of kilometers travelled to perform somewhere in French no man's land for 300 euros, with no travel allowance. I ask myself how useful it is to go and play somewhere else, and the desire for something unfamiliar is always stronger than the sense of reality. An exhaustion from always having a meagre wage while the cost of living is rising. Exhaustion from always having to apply for a premium reduction from the health insurance company, because without it I can really pack it in. Exhaustion from having to create tons of dossiers in order to realize my projects.

And speaking of projects: Recently, at the age of 47, I have been filled with undisguised anger at the rejection of a grant that puts a very personal performance, the fruit of my work over the last four years, in jeopardy because "we can only consider a third of the applications submitted". I am aware that there is not an infinite amount of money available for culture. Talking to musician friends, I hear that some of them put their entire meagre savings on the table to produce and manufacture an album. (Needless to say, we don't get a penny from Spotify and the like). Others squander a small inheritance "so as not to abandon projects altogether", others actually quit in disgust and still others burn out. Everyone is suffering. More and more. In silence. Invisible.

I studied at the HEMU in Lausanne and completed a master's degree in baroque cello at the HEM in Geneva. I have been a professional musician for 23 years. There are months when I earn 400 francs because I can only play one concert in 30 days. Yes, I could teach, I could play in an orchestra. But that doesn't suit me at all. I like writing music, composing for projects, giving concerts. That's why I learned this profession.

It takes time to create music, practice on the instrument, promote concerts, do administrative work (more than half of my time). After a day of lessons, who has the energy to sit down in their practice room and find the inspiration for an original composition? Because, in addition to being a musician, you also have to learn to sell yourself. I can say that my work takes up more than 100 percent of my time. To be clear: I only do that: work. And for free.

It goes without saying that rehearsals are also unpaid. Just like the work on the instrument, composing, putting together a concert program, the hours spent on the computer to put together a budget or a project presentation. Only the concert is paid for. And the travel expenses, often if you fight for them. As the excellent study by Marc Audétat and Marc Perrenoud, published by Stéphanie Arboit in Le Temps on April 25, shows, the average fee for jazz and new music is 300 francs. Even if you perform every weekend, which (I believe) hardly any Swiss artist can do, it is extremely difficult to make a living ... The beautiful drawings by Maimuna (on Instagram, April 25) show this very clearly.

Isn't it sad and shocking that we have to say to ourselves: We do vocational training, go to university, learn self-taught or via other educational paths, we spend our lives making music and can't make a living from it. What I also find unfortunate in our profession is the unfair competition. Since we're in such an unfortunate situation, I don't think you're doing the profession a service if you're prepared to play somewhere for less than 300 francs. It gives the impression that our services are worthless. Hence the question: what is a professional musician? Someone who lives from their art, has studied at a school and has no other income than music?

Over the past few days, I have spoken to many musicians. And everywhere I go I feel this exhaustion, this healthy anger, this dejection. I think we have to do something.

What conclusions can be drawn from the above-mentioned study? How do we become visible? What should we do to be heard? How do we join forces? And above all: what do we propose to change things?

This morning I am tired of my/our invisibility."