"Culture and digitization" - the results

At the suggestion of the Swiss Music Council, the TA-SWISS Foundation commissioned three sub-studies on the topic of "Culture and digitalization". Some of the results were surprising.

Changes in the cultural sector due to digitalization have been on the Swiss Music Council's mind for some time. However, the pandemic drastically demonstrated how quickly entire sectors of the economy can be threatened - and how quickly digitalization can create a replacement, at least in some areas. The question of the opportunities and risks offered by digital developments suddenly became very topical.

Against this backdrop, the TA-SWISS foundation, which investigates the opportunities and risks of new technologies on behalf of the federal government, issued a call for tenders in December 2021 for a study on the topic of "Culture and digitalization". The first section of this call for proposals outlines the topic: "The interdisciplinary study aims to assess the opportunities and risks of the effects of digitalization on culture and our social development. It will attempt to answer technical, legal, social, political, economic, ecological and ethical questions. Due to this diversity, it may also consist of several sub-projects."

Three sub-studies - Digitization in music as an important topic

The Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts HSLU, the Swiss Music Council SMR and the Dezentrum Zürich were awarded the contract. While HSLU dealt with the social, economic, political and legal effects of digitization on various cultural areas, the other two studies focused on art (Dezentrum) and music (Swiss Music Council SMR). The studies are available both in book form and online.[1] The studies should be particularly valuable for professional associations, as they provide information on the extent to which digitization should be a topic in association activities.

The SMR study on the music sector focused on the following questions:

- How do those affected assess digitalization in general? Does the perception of risks predominate or are the opportunities rather emphasized?

- Which digital technologies are used and how are they assessed?

- What effects does digitalization have on various aspects of music creation? For example, what about the organization and staging of concerts, the recording and marketing of music or the opportunities to purchase music?

- What future developments are expected? Here, for example, questions are asked about the development of live performances, music lessons or the diversity of music creation.

- Do those affected see a need for political action - and if so, what kind?

In order to answer these questions, an online survey was conducted to gather the opinions of organizations active in the Swiss music sector as well as music professionals (professional and amateur musicians, teachers, employees of organizations active in the music sector).

Optimism and confidence prevail

The surveys yielded some surprising findings. The fact that only just over 6 percent of music professionals and less than 2 percent of organizations in the music sector see digitalization as predominantly a risk could not have been expected in light of the experiences during the pandemic. Overall, the organizations prove to be slightly more optimistic about digitization than the music creators, among whom the amateurs emphasize the opportunities slightly more often than the professional music creators.

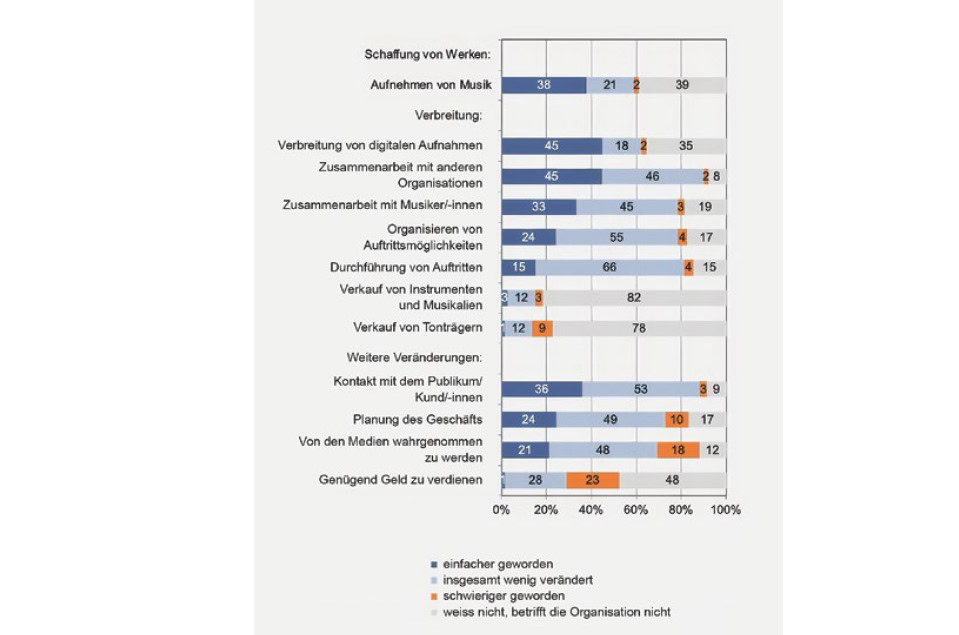

With regard to the use of digital technologies, it is clear that they are widely used by both music professionals and organizations and that there is a remarkable openness to new developments in the future. Against this background, it is not surprising that the respondents perceive digital technologies as making musical life easier rather than more difficult. Figure 2 below shows this finding based on the responses of the organizations.

In many of the aspects surveyed, the organizations have hardly changed, but especially when it comes to recording music, distributing digital recordings and collaborating with other organizations, the proportion of those who note simplifications is considerable. Only in terms of media perception and earning opportunities did around a fifth of the organizations face greater difficulties. The fact that almost half of the organizations did not comment on "earning money" is due to the fact that many clubs and associations took part in the survey for which this objective is not a high priority.

The study focused not only on current developments, but also on future prospects. When music creators and organizations active in the music sector were asked how they assess the future of various parts of the music sector, their overall assessment was rather optimistic. In the perception of a majority of respondents, digitalization will lead to a more diverse music world in which live music will continue to play an important role. However, pessimistic attitudes prevail with regard to the future of music clubs and instrumental lessons, and a significant proportion of music professionals and organizations fear that musical life could become harder in the future.

From the Music Council's perspective, the question of the desirability of political intervention in the context of music and digitalization was important, as exerting influence in Bern is one of the SMR's core tasks. Here, too, the answer was different than expected. The chart below shows that most music professionals and organizations do not see any immediate need for intervention:

However, both the detailed analysis and the many individual comments showed that this finding needs to be differentiated and should not be taken to mean that there is no need for action. This is because digitalization exacerbates existing problem areas both within the value chain (creation, distribution, reception) and in the areas of amateur and professional music creation, music education and the music industry.

Recommendations for action based on the overall study

One of the tasks of the TA-SWISS Foundation is to formulate recommendations for policymakers based on the results of studies. With regard to digitalization in the cultural and music sector, these include

- The cultural sector, together with the public sector and society, must take a proactive approach to digitalization in order to be prepared for further developments. Institutions and associations have an important role to play here.

- Digitization should be placed on the agenda of the National Cultural Dialogue as a multi-year priority.

- The "Fair income conditions in the digital environment" measures provided for in the 2025 - 2028 Culture Dispatch should be implemented quickly.

- Taking a proactive approach to digitalization also means establishing it as an integral part of education and training. The associations can also play an important role here.

- Copyright is a perennial issue, but rapid developments such as in artificial intelligence are giving rise to completely new questions. The legal framework should therefore be constantly reviewed and adapted.

- Amateur clubs, especially in music and culture, form the humus on which musical/cultural life can flourish. They should therefore continue to receive targeted support at all levels of government. In addition, constant monitoring is needed in order to closely observe the development of this important form of social coexistence.

- Music education is already under pressure today due to social developments. Digitalization is intensifying this pressure, which is why music professionals see difficult times ahead for music education. To counteract this, teachers must be enabled to master digital tools and use them in a targeted manner.

Former Federal Councillor Moritz Leuenberger, who chaired the group accompanying the three studies, commented on the subject as follows[2]:

"Digitalization is shaping the way we think and feel. It has become an indispensable servant of our culture, but at the same time has long since taken up the baton. To prevent it from becoming the sole conductor, we are required to sound out its opportunities and dangers and set the pace ourselves."

A special feature of this study is that the central content can be experienced interactively on a platform, with one interactive room per sub-study: https://www.proofofculture.ch/

Footnotes

1st TA-SWISS publication series (ed.)(2024): Culture and digitization. Zollikon: vdf. The text and a summary can be found online at: https://www.ta-swiss.ch/kultur-und-digitalisierung

2 Cf. the TA-SWISS publication mentioned above, p. 7.