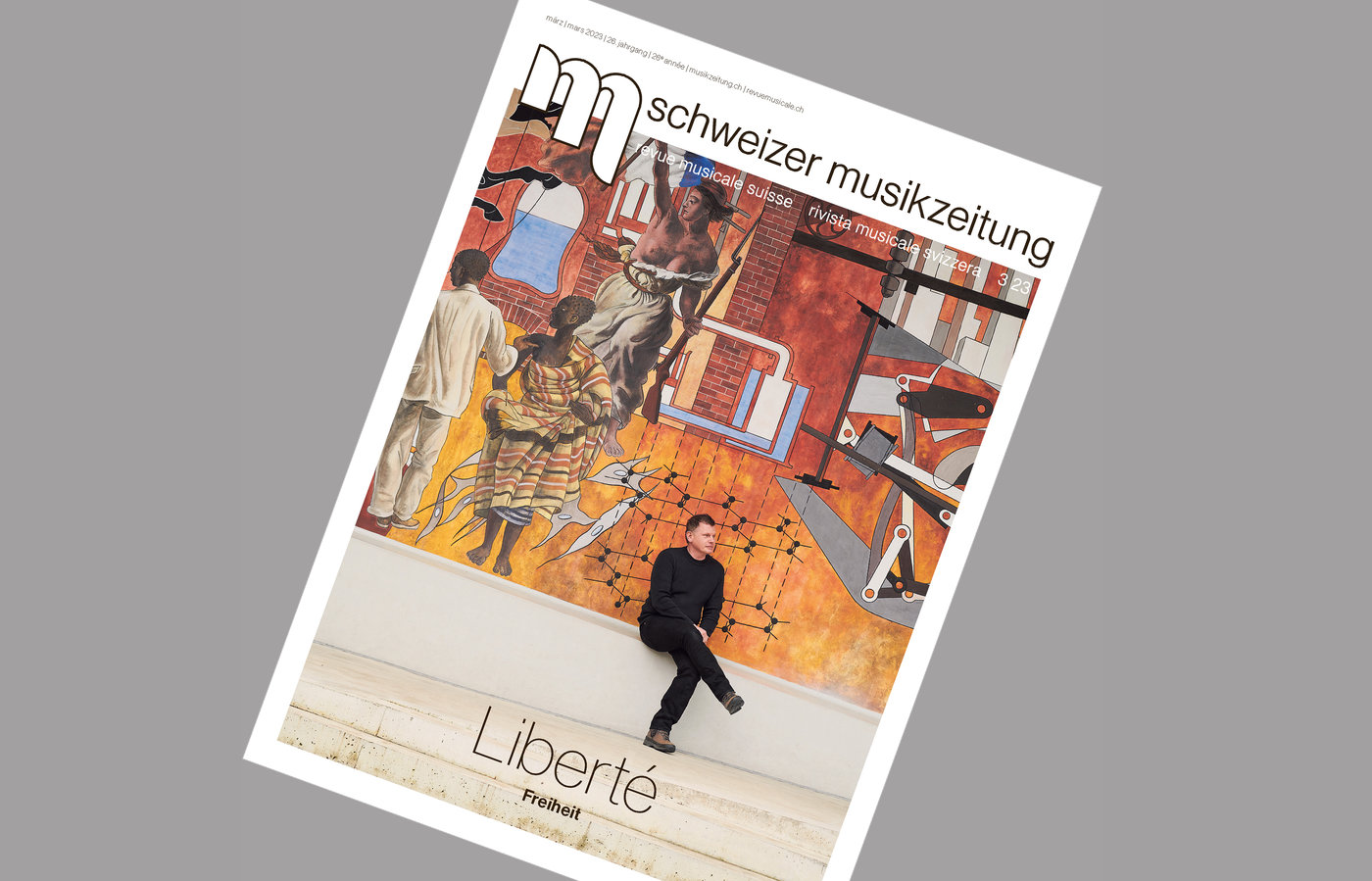

Outstandingly interpreted works at the Basel Composition Competition

The fourth edition of the Basel Composition Competition focused on previously unknown composers from different generations. The Brazilian Leonardo Silva won the first prize of 60,000 Swiss francs.

This year, the Basel Composition Competition (BCC) took place from February 9 to 12 under normal conditions, which was very much appreciated by all participants. In contrast to the composition competition at the Geneva Concours a few months ago, where only three selected works were played in the final, twelve compositions for symphony and chamber orchestra were performed in Basel. The Basel Sinfonietta, the Basel Symphony Orchestra and the Basel Chamber Orchestra each performed four works on three evenings at the Don Bosco Music and Culture Center under the direction of Jessica Cottis, Clemens Heil and Sylvain Cambreling.

To get straight to the point: All three ensembles were very well prepared and motivated, which guaranteed an adequate performance of each composition. Even the most technically demanding tasks were mastered impressively.

Stylistic breadth, geographical gaps

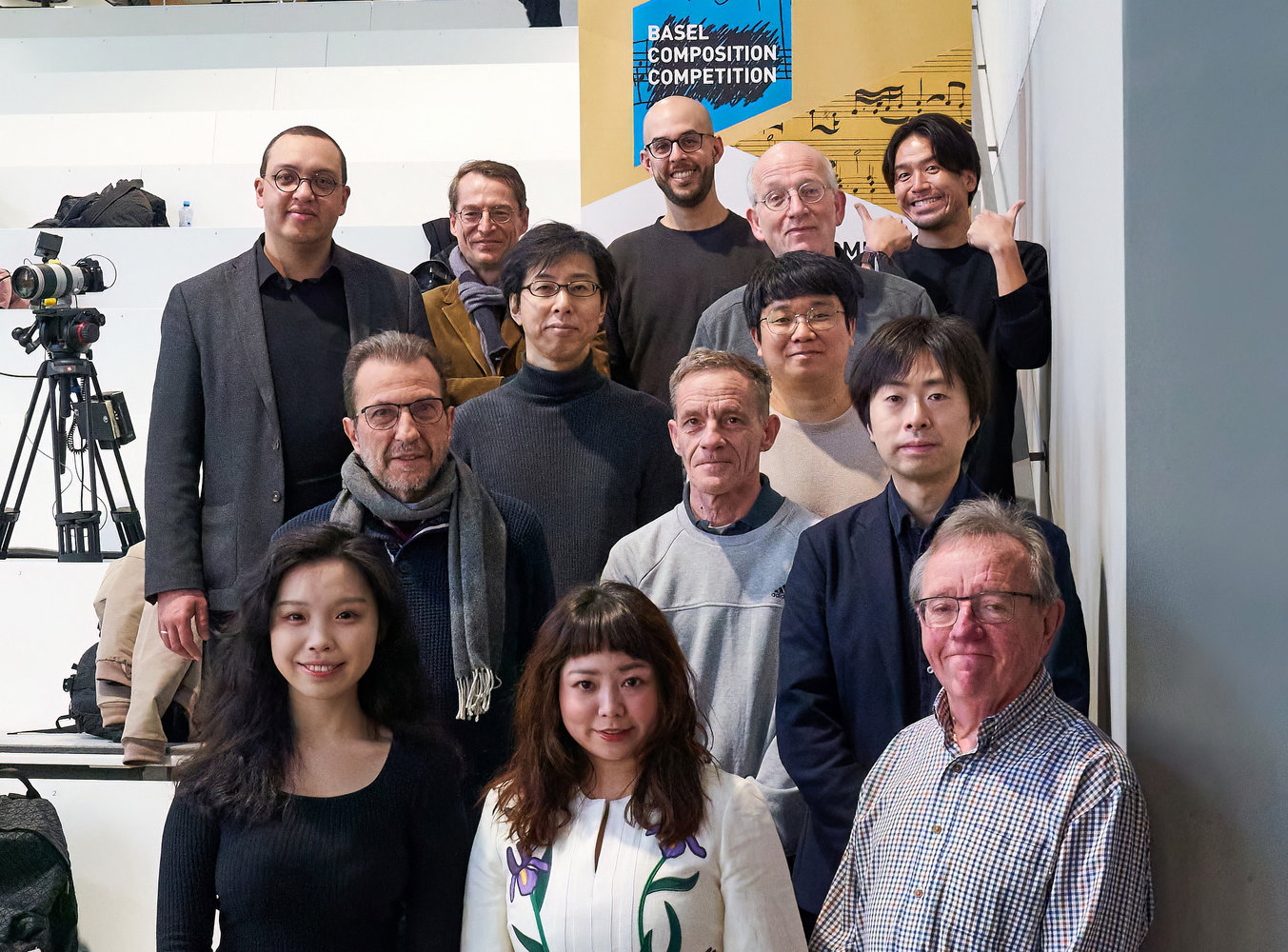

There are no restrictions on the age or nationality of participants at the BCC. This year's jury consisted of the composers Michael Jarrell (chair), Toshio Hosokawa (whose new violin concerto was premiered by the Berliner Philharmoniker on March 2, 2023), Luca Francesconi, Andrea Scartazzini and the director of the Paul Sacher Foundation, Florian Besthorn. Isabel Mundry had been involved in the selection process in October but, like Rebecca Saunders, had to cancel her participation due to illness.

Without knowing the countries of origin of the composers of all the works submitted, it is surprising that none of the pieces performed came from North America or Eastern Europe, while the majority were from East Asia. Stylistically, however, they were quite different, their titles often enigmatic (Metempsychosis, e-e IV, Opus reticulatum, Incognita_C) and some quite uninteresting. Once again, it turned out that a complex score with extreme fanning out of the voices is no guarantee of a special sound, just as little as the personal strokes of fate mentioned in the explanations of the works or the reference to well-known visual artists or poets, from whose brilliance something should radiate onto the respective piece.

Amazing ranking list

Choosing the works for the final concert must have been somewhat easier than determining the final ranking list. It was pleasing to see that, although there was perhaps no masterpiece among them, each of the five works played in the finale on February 12 was gladly heard a second time.

The Japanese Nana Kamiyama (*1986) received a third prize (CHF 7500 each) for Umbilical cord for chamber orchestra, a work influenced by the sound of Japanese instruments, which combines noise and defined pitches in an attractive way. Also chameleon by South Korean composer Jinseok Choi (*1982) was awarded third prize. Inspired by traditional Korean music, this virtuoso and powerful composition is based on several independent musical cells. These are arranged in a contrasting manner and create overlapping changes in sound and color.

The second prize of 25,000 Swiss francs was won by Masato Kimura from Japan, born in 1981, for -minusIX for five string quartets and ensemble. This interestingly scored work is part of a series that the composer calls "negative acoustic space". Its sound is created on the basis of negative aspects of phenomena such as instability, silence, ambiguity and slowness. Derived from this - and not easy to understand - a "sound fog" characteristic of the work is created.

The main prize, donated by the Isaac Dreyfus Bernheim Foundation, was awarded to the Berlin-based Brazilian composer Leonardo Silva (*1989) for his piece Lume (musica d'immenso I). It is inspired by a short poem by the Italian poet Giuseppe Ungaretti. Certainly not a bad work, but it did not stand out from the other compositions in any way. Rather, one could say that its sound world has already been encountered in many other pieces of the classical avant-garde, such as those by György Ligeti. The fact that works by Wagner, Stravinsky or Boulez also begin with an E flat, like his own, is something the composer would probably have done better to keep to himself.

The works that did not receive a prize were Gou Chen IV the 22-year-old Chinese woman Jin-Han Xiao and Beyond of the Englishman John Weeks (*1949) was the most remarkable. The young Chinese composer's piece, which is very difficult to play and also imitates electronic effects, is an incredible eruption of sound and made most of the other works look pale. Beyond for chamber orchestra by Weeks, which comes from a completely different world, was one of the few compositions that attached great importance to the instrumentation. Alto flutes, cor anglais (with a wonderful solo by Matthias Arter), bass clarinets and contrabassoons lent the work an extraordinary aura.

Anchoring in the city

A special feature of the BCC is certainly that the organizers attach great importance to anchoring the competition in the city. For example, several composers worked together with school classes, talked about their lives and explained their works and composition methods. Chamber music works by jury members Toshio Hosokawa and Rebecca Saunders were also performed in two pre-concerts. The ensembles of the Hochschule für Musik, rehearsed by Marcus Weiss, shone with outstanding interpretations of extremely interesting works.

The fifth edition of the Basel Composition Competition will take place in February/March 2025.