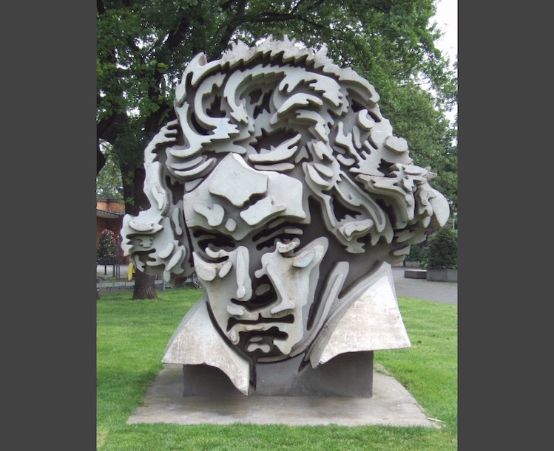

Bettina Skrzypczak on her composition "Oracula Sibyllina", on artistic commitment and the question of how life could go on after Corona.

Bettina Skrzypczak lives in Riehen and teaches composition, theory and music history at the Lucerne School of Music. In February, she was awarded the Heidelberg Women Artists' Prize 2020, and in May she received the Canton of Aargau's composition grant for 2020. Musikkollegium Winterthur, led by Pierre-Alain Monot over five years ago, launched its Oracula Sibyllina for mezzo-soprano (Mareike Schellenberger) and orchestra was the result of years of studying ancient oracles and prophetesses. Today, the work is more topical than ever before.

Bettina, your composition begins with the words: "I am Sibylle." So first the question: Who is this Sibyl?

This is a fictional character.

Interesting! And how is it put together?

I need to expand a little on this. The Sibyls were wise women who prophesied - female prophets. They were first mentioned in antiquity by Heraclitus. The Roman author Varro names ten sibyls, each with their own prophecies. Their prophecies do not refer to historically localizable people or facts, but to human existence in general, mostly in the form of warnings. The texts are timelessly topical, and that impressed me. I was particularly interested in two of these sibyls, the Sibyl of Erythrai and the famous Sibyl of Cumae from near Naples. My text is based on their statements.

That sounds like a long development process.

I worked on the subject matter for months and gave it a lot of thought. The text compilation was the first stage of the composition, and the music grew together with the text, albeit initially only in my head. This is how the portrait of a Sibyl emerged as a result of my imagination. She embodies everything I discovered and felt while studying the texts.

How would you characterize this Sibyl?

The characterization follows a precise dramaturgy. There are three phases, and each ends with the warning appeal: "Listen!" In the first part, she introduces herself: "I am Sibyl, Phoibos' prophesying servant. I am the daughter of the nymph Naia." This is the crux of the matter: she is the daughter of an earthly natural being and at the same time the servant of Phoibos Apollo, the 'shining one', who is equated with the sun god Helios. This means that in her case there is the moment of the earthly, the transient, and the moment of the divine, the light. This inner tension or even conflict fascinated me.

What is the musical character of this first part?

The basic trait is lyrical. The melodic line is in the foreground here, cantabile as a symbol of humanity. There is something poignant when she tells of her fate.

And the second phase?

Here, the Sibyl appears as a disappointed rebel and becomes very emotional. She says: "You don't listen to my words and call me a raging lying Sibyl - I'm warning you!"

And then the whole thing explodes.

The third part of the text takes us into a completely different dimension. This is the phase of ecstasy and the climax of the work. The Sibyl enters a state in which she can no longer control herself. She loses her personal traits, becomes the mouthpiece of supernatural forces and sees terrible things. Here, everything in the music is torn apart, chopped up; the cantabile associated with her human feelings is gone, the noisy prevails. Then she falls silent; she is horrified by what she sees and the music stops. There is an emptiness. But there is a twist at the end: The sibyl sings once more, "Listen!" The cantabile line symbolizes a return to the human - a signal that hints at salvation.

The word "hear" occurs remarkably often.

I understand Oracula Sibyllina as a composition about listening: Listening as listening and as a symbol for the concentrated experience of inner and outer reality, as comprehensive attention to the world that is given to us and that we must not destroy.

With this piece, you have also drawn a portrait of an incredibly complex female figure.

It is a medium that has two sides: one human and one that we do not understand.

A kind of female archetype with all its contradictions.

Maybe.

The dramatic character of the figure also results from this inner conflict. "Oracula Sibyllina" is conceived as a monodrama. Have you already thought about a staged performance?

Yes, of course. The voice in particular, with its gradations from speaking to chanting to highly expressive singing, calls for a scenic performance. The division of the orchestra into three spatially separated groups supports the drama. It becomes a resonance chamber for the voice.

The third part opens up dimensions that are rarely found in music today. The Sibyl describes an apocalypse in the form of a cosmic battle of the stars: "God let them fight, and Lucifer directed the battle." This image is also presented in an incredibly gripping musical way.

There are existential human thoughts that cannot be described. That's why I let the Sibyl speak, observe her from the outside and experience through her that something incomprehensible is happening. She can only describe it in stammering words. I see what is happening to her, but I don't dare to enter these realms myself.

Nevertheless, you are the composer and you formulate it.

I am only giving a kind of outline of the huge event.

You pointed out that the Sibyl also has a light side. But apart from the first part, this is actually a very dark piece. Everything leads up to this third part, the battle of the worlds.

I don't see this as a hopeless situation. The ending is open and also leaves room for hope. But I wanted to go to the limit to emphasize the seriousness of the warning.

Your commentary on your work from 2015 ends with a quatrain: "Who are you, Sibylle, you homeless? / I want to stand by you / On your path of endless searching / In your flight from darkness." You obviously identify strongly with this character.

The dilemma in which she finds herself took me along with her: She is a very sensitive person who perceives the world in a differentiated way, and at the same time she carries the fateful burden of having to see things that others don't see and is not taken seriously. She wants to say something, but nobody listens, and so I wanted to empathize with her. When I composed the apocalypse part, I was completely exhausted, even physically. It took a lot of energy. There is nothing free in this music.

The communication aspect is obviously very important to you.

When I deal with a text like this, I naturally want to say something. I feel the need to speak, to make my position clear as a person living today. That certainly applies to everyone who is artistically active.

"Oracula Sibyllina" was created in 2014-15 and premiered in Winterthur on May 21, 2015. Compared to today, the world seemed almost in order back then. Since then, many problems have come to a head. How is it that you wrote a play with such a catastrophic tendency at a time that was still relatively calm?

The figure of the Sibyl had been on my mind for years. In 2003, the Quartet noir played my composed improvisation entitled Weissagung at the Lucerne Festival, which already contained some of the sentences of the current text; the double bassist Joëlle Léandre did a great job of portraying the wildness of the Sibyl. That continued to work in the back of my mind. And then I have also been observing the disturbing changes in society and coexistence for many years, and these have increased in recent years. These were the small pieces of the mosaic that slowly came together to form the picture that then flowed into the composition.

Five years later, in the middle of the coronavirus crisis

At its premiere, "Oracula Sibyllina" was still primarily perceived as a purely aesthetic event. And now, five years later, we are in the midst of the disaster of the coronavirus crisis and have the feeling that the horrifying vision of this sibyl concerns us.

I have to say, sometimes I am amazed myself that my hunches or ideas come true after a long time. This confirms my view that although we humans recognize certain developments intuitively or perhaps even rationally, we don't want to admit that they really exist. We have always believed that we could explain everything and thus control the world, and have overlooked the fact that there are areas of the human being that are completely irrational. These areas come to the fore in the Sibyl when she prophesies. And that is also where art can come in to shed light on the darkness. The voice of the sibyl, which has become the inner voice of our conscience, can guide us.

The unexpected topicality of this work reminds me from afar of the story of Gustav Mahler, who wrote the "Kindertotenlieder" at a happy time in his life, and three years later his daughter died. Do artists have a seventh sense?

If that is the case, then perhaps it has to do with the artist's working method. He concentrates on his work for months and years, and that sharpens his perception in an extreme way. When I compose, I perceive everything much more intensely, even everyday things. I hear more intensely, I understand people more intensely. There is an opening of the heart and of the mind. And perhaps this allows you to see further into the future than other people. I believe that every artist has the ability to perceive the world so intensely and to take part in the changes. Much of what I experience as a contemporary concerns me incredibly strongly, and music is the medium in which I communicate my feelings.

This brings us to today's much-discussed question: should artists get involved in social issues?

In any case, absolutely. I have my difficulties with what is somewhat narrowly called "political music", but a connection to reality can arise in many different ways. I'm not one of those people who say: yes, that's the way it is and there's nothing we can do. Something is burning inside me, I want to make a difference with my music and change something. I think strong voices are the only way to get things moving. That's why this Sibylle impresses me. She pushes herself to her limits and risks a lot in the process. In doing so, she makes it possible for the light to come again in the end after the prophecies that have often been so terribly fulfilled.

Should a composer react directly to the corona problem?

One of my students has already asked me whether I don't feel the need to write such a work. But that still seems too early to me, and I don't believe in such a reflex at the push of a button. We are still in the midst of it and have experiences that need to be processed first. We need time to reflect. But it is absolutely necessary to deal with these unprecedented events artistically sooner or later.

Apart from the material consequences, what are the effects of the coronavirus crisis on individual artists?

Art consists of exchange, it is an act of communication. Like everyone else, it's important for me to be able to communicate with the listener and the performer, and that's not possible at the moment. Corona will of course be over at some point. But I emphasize the moment of reflection again, because only then can we draw the consequences and react accordingly. The worst thing would be to think that it's all over now and we can carry on as before.

What would you wish for afterwards?

That we overcome our egoism and listen to each other more. That we develop more sensitivity towards other people, including our neighbors, and rejoice in what we have been given, in the whole present in which we live. That we learn to appreciate what we have again and not just think about what we don't yet have or what we still want to achieve.